Sleek Desk Lamp Changes Colors Based on Sun Position

[Connor] was working on a project for his college manufacturing class when he came up with the idea for this sleek desk lamp. As a college student, he’s not fond of having his papers glowing brightly in front of him at night. This lamp takes care of the problem by adjusting the color temperature based on the position of the sun. It also contains a capacities touch sensor to adjust the brightness without the need for buttons with moving parts.

The base is made from two sheets of aluminum and a bar of aluminum. These were cut and milled to the final shape. [Connor] found a nice DC barrel jack from Jameco that fits nicely with this design. The head of the lamp was made from another piece of aluminum bar stock. All of the aluminum pieces are held together with brass screws.

A slot was milled out of the bottom of the head-piece to make room for an LED strip and a piece of 1/8″ acrylic. This piece of acrylic acts as a light diffuser. Another piece of acrylic was cut and added to the bottom of the base of the lamp. This makes for a nice glowing outline around the bottom that gives it an almost futuristic look.

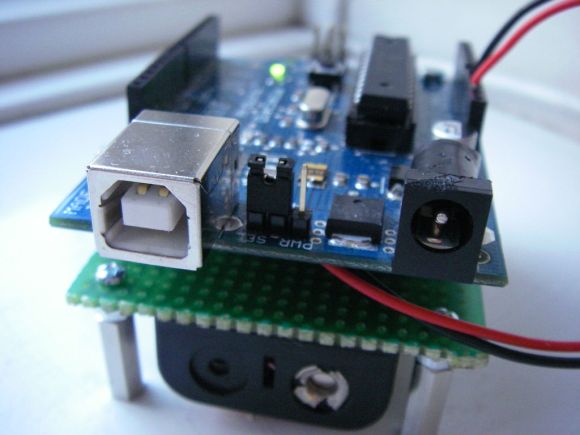

The capacitive touch sensor is a pretty simple circuit. [Connor] used the Arduino capacitive touch sensor library to make his life a bit easier. The electronic circuit really only requires a single resistor between two Arduino pins. One of the pins is also attached to the aluminum body of the lamp. Now simply touching the lamp body allows [Connor] to adjust the brightness of the lamp.

[Connor] ended up using an Electric Imp to track the sun. The Imp uses the wunderground API to connect to the weather site and track the sun’s location. In the earlier parts of the day, the LED colors are cooler and have more blues. In the evening when the sun is setting or has already set, the lights turn more red and warm. This is easier on the eyes when you are hunched over your desk studying for your next exam. The end result is not only functional, but also looks like something you might find at that fancy gadget store in your local shopping mall.

Filed under: Arduino Hacks

Yes. This one moves on its own. It’s a robotic woodworking workbench that lifts the workpiece and table up to a comfortable position. The lifting mechanism is a quartet of Acme threaded rods all powered by an Arduino-controlled stepper motor linked together with sprockets and chain. There’s a remote control to raise and lower the bench, and a few batteries tucked behind the mechanics to allow for off-grid operation.

Yes. This one moves on its own. It’s a robotic woodworking workbench that lifts the workpiece and table up to a comfortable position. The lifting mechanism is a quartet of Acme threaded rods all powered by an Arduino-controlled stepper motor linked together with sprockets and chain. There’s a remote control to raise and lower the bench, and a few batteries tucked behind the mechanics to allow for off-grid operation.

We’re well past the time when Halloween costume submissions stop hitting the tip line, but like ever year we’re expecting a few to trickle in until at least Thanksgiving. Remember, kids: documentation is the worst part of any project.

We’re well past the time when Halloween costume submissions stop hitting the tip line, but like ever year we’re expecting a few to trickle in until at least Thanksgiving. Remember, kids: documentation is the worst part of any project.