Gaming on an Arduino Uno Q in Linux

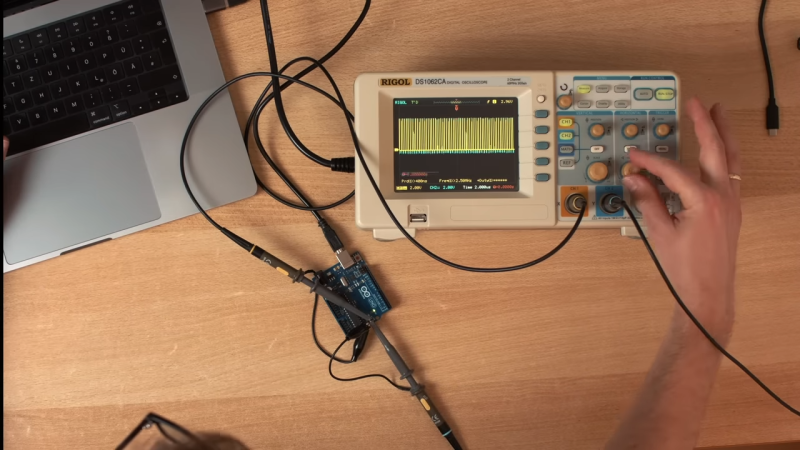

After Qualcomm’s purchase of Arduino it has left many wondering what market its new Uno Q board is trying to target. Taking the ongoing RAM-pocalypse as inspiration, [Bringus Studios] made a tongue-in-cheek video about using one of these SoC/MCU hybrid Arduino boards for running Linux and gaming on it. Naturally, with the lack of ARM-native Steam games, this meant using the FEX x86-to-ARM translator in addition to Steam’s Proton translation layer where no native Linux game exists, making for an excellent stress test of the SoC side of this board.

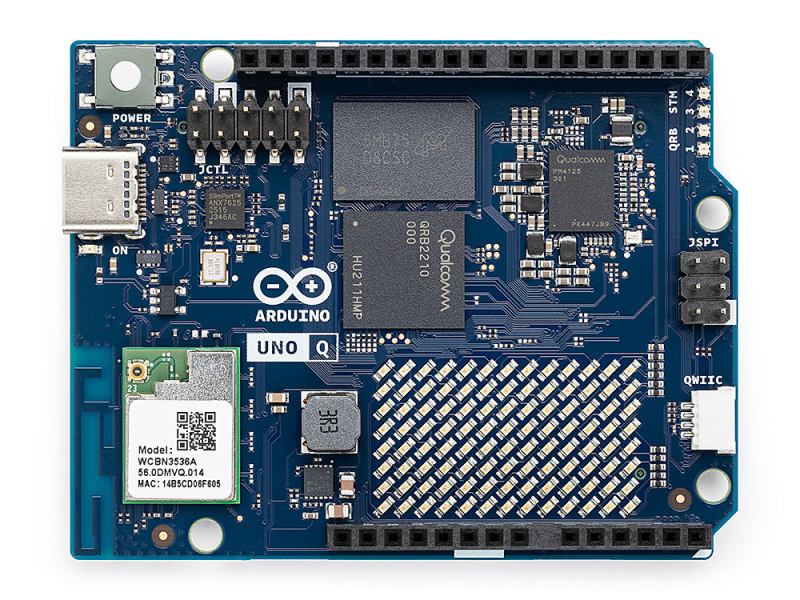

We covered this new ‘Arduino’ board previously, which features both a quad-core Cortex-A53 SoC and a Cortex-M33 MCU. Since it uses the Uno form factor, all SoC I/O goes via the single USB-C connector, meaning that a USB-C docking station is pretty much required to use the SoC, though there’s at least 16 GB of eMMC to install the OS on. A Debian-based OS image even comes preinstalled, which is convenient.

With a mere 2 GB of LPDDR4 it’s not the ideal board to run desktop Linux on, but if you’re persistent and patient enough it will work, and you can even play 3D video games as though it’s Qualcomm’s take on Raspberry Pi SBCs. After some intense gaming the SoC package gets really quite toasty, so adding a heatsink is probably needed if you want to peg its cores and GPU to 100% for extended periods of time.

As for dodging the RAM-pocalypse with one of these $44 boards, it’s about the same price as the 1 GB Raspberry Pi 5, but the 2 GB RPi 5 – even with the recent second price bump – is probably a better deal for this purpose. Especially since you can skip the whole docking station, but losing the eMMC is a rawer deal, and the dedicated MCU could be arguably nice for more dedicated purposes. Still, desktop performance is a hard ‘meh’ on the Uno Q, even if you’re very generous.

Despite FEX being a pain to set up, it seems to work well, which is promising for Valve’s upcoming Steam Frame VR glasses, which are incidentally Qualcomm Snapdragon-based.