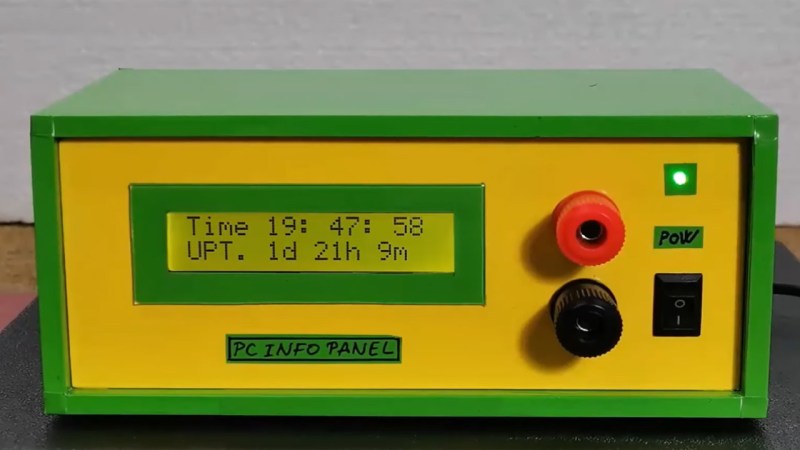

Arduino-Powered Info Display For Your Windows Computer

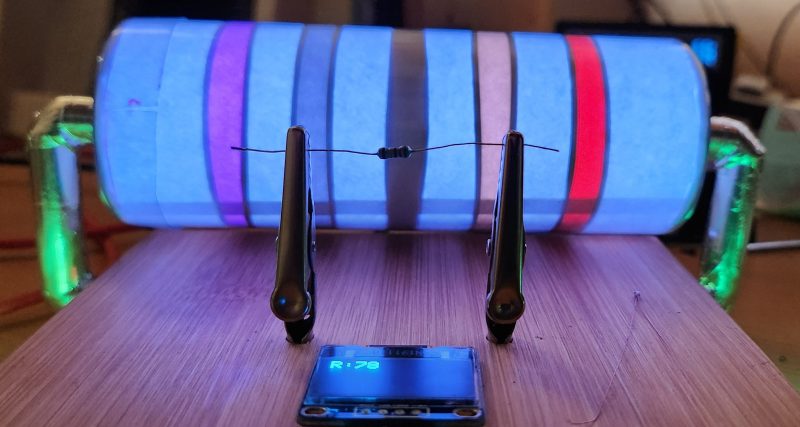

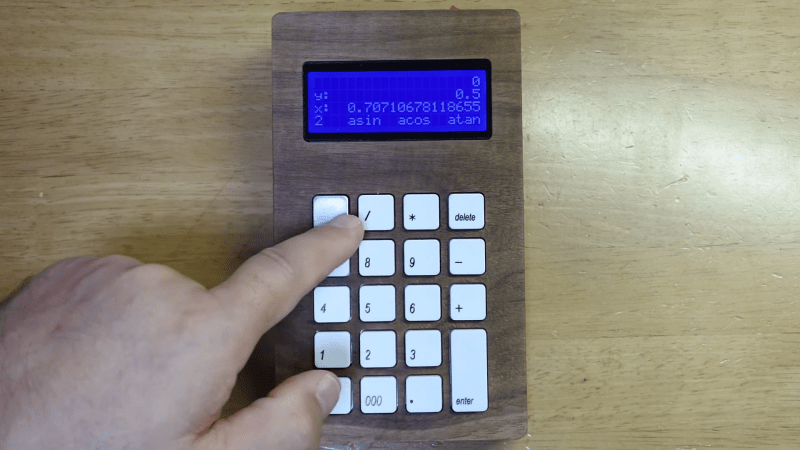

If you’ve been pining for a retro-chic 16×2 LCD display to enhance your Windows computing experience, then [mircemk] has got you covered with their neat Windows-based LCD Info Panel.

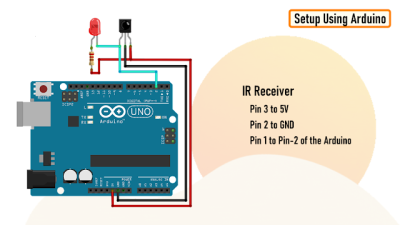

Your everyday garden variety Arduino is the hero here, sitting between the computer’s USB port and the display to make the magic happen. Using the ‘LCD Smartie‘ software, the display can serve up some of your typical PC stats such as CPU and network utilization, storage capacity etc. It can also display information from BBC World News, email clients, various computer games and a world of other sources using plugins.

It’s clear that the intention here was to include the display inside your typical PC drive bay, but as you can see in the video below, this display can just about fit anywhere. It’s not uncommon to see similar displays on expensive ‘gamer’ peripherals, so this might be an inexpensive way for someone to bring that same LED-lit charm to their next PC build. You probably have these parts sitting in your desk drawer right now.

If you want to get started building your own, there’s more info over on the Hackaday.io page. And if PC notifications aren’t your jam, it’s worth remembering that these 16×2 displays are good for just about anything, like playing Space Invaders.