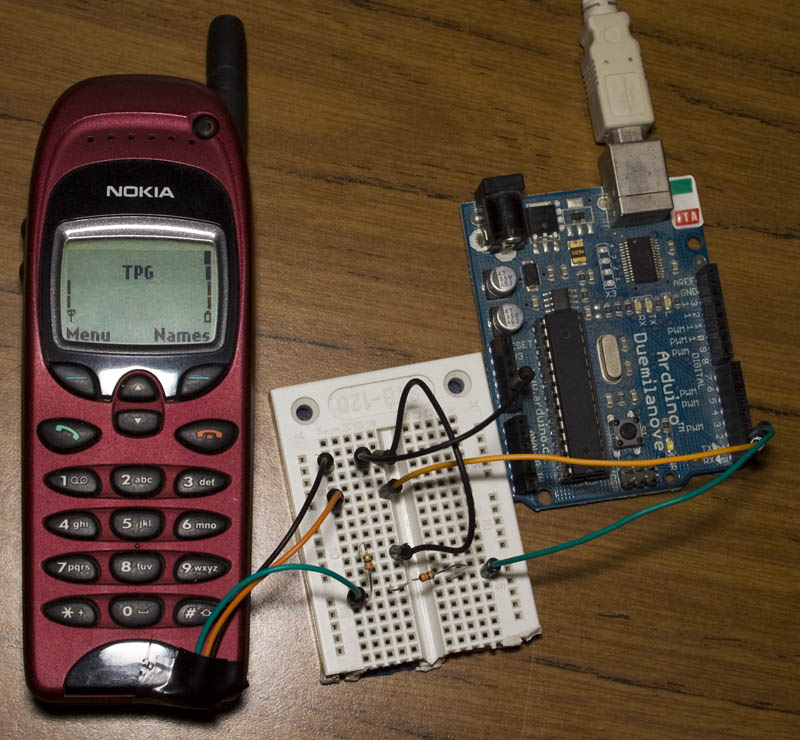

It makes an Arduino look like a 555. A 364 Mhz, 32 bit processor. 8 MB RAM. GSM. Bluetooth. LCD controller. PWM. USB and dozens more. Smaller than a Zippo and thinner than corrugated cardboard. And here is the kicker: $3. So why isn’t everyone using it? They can’t.

Adoption would mandate tier after tier of hacks just to figure out what exact hardware is there. Try to buy one and find that suppliers close their doors to foreigners. Try to use one, and only hints of incomplete documentation will be found. Is the problem patents? No, not really.

[Bunnie] has dubbed the phenomenon “Gongkai”, a type of institutionalized, collaborative, infringementesque knowledge-exchange that occupies an IP equivalent of bartering. Not quite open source, not quite proprietary. Legally, this sharing is only grey-market on paper, but widespread and quasi-accepted in practice – even among the rights holders. [Bunnie] figures it is just the way business is done in the East and it is a way that is encouraging innovation by knocking down barriers to entry. Chinese startups can churn out gimmicky trash almost on whim, using hardware most of us could only dream about for a serious project.

He contrasts this with the West where only the big players like Apple and Google can step up to the plate. Everyone else is forced to use the embarrassingly obsolete hardware we are all familiar with. But [Bunnie] wants to get his foot in the door. “Can we find a way to still get ahead, yet still play nice?” he asks.

Part of his solution is reverse engineering so that hardware can simply be used – something the EFF has helped legally ensure under fair use. The other half is to make it Open Source. His philosophy is rooted in making a stand on things that matter. It is far from a solid legal foundation, but [Bunnie] and his lawyers are gambling that if it heads to a court, the courts will favor his side.

Part of his solution is reverse engineering so that hardware can simply be used – something the EFF has helped legally ensure under fair use. The other half is to make it Open Source. His philosophy is rooted in making a stand on things that matter. It is far from a solid legal foundation, but [Bunnie] and his lawyers are gambling that if it heads to a court, the courts will favor his side.

The particular board targeted is the one described above – the MT6260. Even spurred by the shreds of documentation he could gather, his company is a 2-man team and cannot hope to reverse engineer the whole board. Their goal is to approach the low-hanging fruit so that after a year, the MT6260 at least enters the conversation with ATMega. Give up trying to use it as a phone; just try to use like the Spark Core for now.

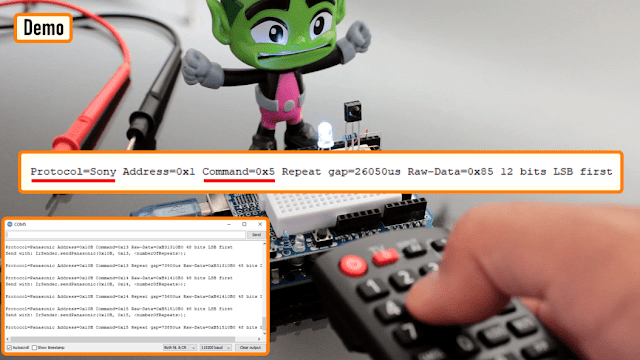

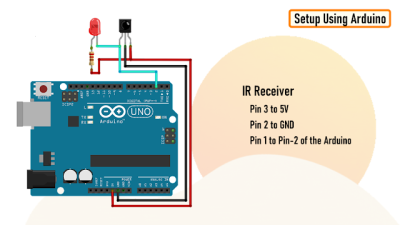

He is already much of the way there. After telling you what is on board and why we would all want to use it, [Bunnie] shows how far he has gone to reverse engineering and describes his plans for the rest. From establishing an electronic “beachhead” base of operations to further probe the device, to X-rays, photos, diagrams and the beginnings of an OS. If this type of thing interests you at all, the meticulous approach and easy-reading of this tech teardown will surely impress and inspire you. Every step of progress requires a new hack, a new solution, a new ingenious way to pry information out.

He is already much of the way there. After telling you what is on board and why we would all want to use it, [Bunnie] shows how far he has gone to reverse engineering and describes his plans for the rest. From establishing an electronic “beachhead” base of operations to further probe the device, to X-rays, photos, diagrams and the beginnings of an OS. If this type of thing interests you at all, the meticulous approach and easy-reading of this tech teardown will surely impress and inspire you. Every step of progress requires a new hack, a new solution, a new ingenious way to pry information out.

We’ve featured some awe-inspiring reverse engineering attempts in the past, but this is something that is still new and relevant. Rather than only exploit his discoveries for himself, [Bunnie] has documented and published everything he has learned. Everyone wins.

Thanks [David] for the tip.

Filed under:

Cellphone Hacks,

hardware,

slider,

teardown

Part of his solution is reverse engineering so that hardware can simply be used – something

Part of his solution is reverse engineering so that hardware can simply be used – something  He is already much of the way there. After telling you what is on board and why we would all want to use it, [Bunnie] shows

He is already much of the way there. After telling you what is on board and why we would all want to use it, [Bunnie] shows