It’s holiday time again! And that means it’s time to break out the soldering iron and the RGB LEDs! If you’re going to make a custom PCB to put those LEDs on, you’ll notice that you get few copies of your PCB in your order, so, might as well design it such that you can combine them all together into a single Sierpinski Christmas Tree, just like [Landon Carter] did.

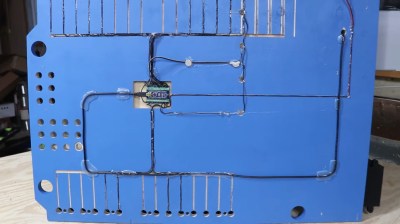

Each PCB “tree” has three connections which can be used as either inputs or outputs by soldering one of two bridge connections on the PCB. The power and signal goes up and down through the tree, rather than across, so the connections go one on the top of the tree and two on the bottom. This way, each tree in the triangle can easily be connected, and each triangle can be easily connected to another. Each individual tree has three WS2812b-mini addressable RGB LEDs and the tree is controlled by an external Arduino.

The first order of 10 PCBs came in, which makes a 9 member tree – next up is a 27 member tree. After that, you’re going to need some pretty high vaulted ceilings in order to put these on the wall. On the upside, though, once the holidays are over, everything can be easily disconnected and packed away with the rest of the decorations. If you, too, are interested in RGB LED decorations, there are a few on the site for your perusal.

Italians have a love of innovation and design and it shows at Maker Faire Rome. In this episode of Make:Cast, I look back at Maker Faire Rome in October 2019 during a pre-Covid time when live events could happen. I was guided through Maker Faire Rome by Alessandro Ranellucci, the curator of Maker Faire Rome, along with Massimo Banzi, co-founder of Arduino. Maker Faire Rome 2020 is happening as a virtual event this weekend.

Italians have a love of innovation and design and it shows at Maker Faire Rome. In this episode of Make:Cast, I look back at Maker Faire Rome in October 2019 during a pre-Covid time when live events could happen. I was guided through Maker Faire Rome by Alessandro Ranellucci, the curator of Maker Faire Rome, along with Massimo Banzi, co-founder of Arduino. Maker Faire Rome 2020 is happening as a virtual event this weekend.

In this case, you’ll be losing all of your nickels to an Arduino Pro Mini. The handle is an upgrade to an earlier slot machine project that uses three 8×8 matrices and a custom driver board. When the spring-loaded handle is pulled, it strikes a micro switch to spins the reels and then snaps back into place. Between each pull, the current score is displayed across the matrix. There’s even a piezo buzzer for victory squawks. We only wish the button under the handle were of the clickier variety, just for the feels. Check out the short demo video after the break.

In this case, you’ll be losing all of your nickels to an Arduino Pro Mini. The handle is an upgrade to an earlier slot machine project that uses three 8×8 matrices and a custom driver board. When the spring-loaded handle is pulled, it strikes a micro switch to spins the reels and then snaps back into place. Between each pull, the current score is displayed across the matrix. There’s even a piezo buzzer for victory squawks. We only wish the button under the handle were of the clickier variety, just for the feels. Check out the short demo video after the break.