Saving Fuel With Advanced Sensors And An Arduino

When [Robot Cantina] isn’t busy tweaking the 420cc Big Block engine in their Honda Insight, they’re probably working on some other completely far out automotive atrocity. In the video below the break, you’ll see them take the concept of a ‘lean burn’ system from the Insight and graft hack it into their 1997 Saturn coupe.

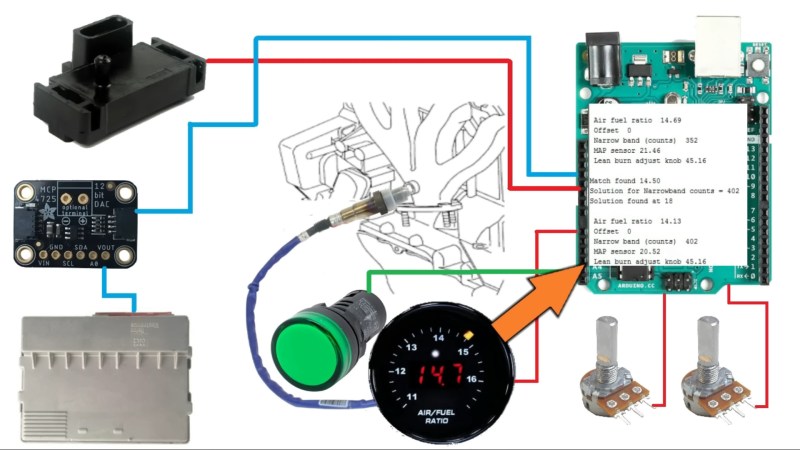

What’s a lean burn system? Simply put, it tricks the car into burning less fuel when it’s cruising under a light load to improve the vehicle’s average mileage. The Saturn’s electronics aren’t sophisticated enough to implement a lean burn system simply, and so [Robot Cantina] did what any of us might have done: hacked it in with an Arduino.

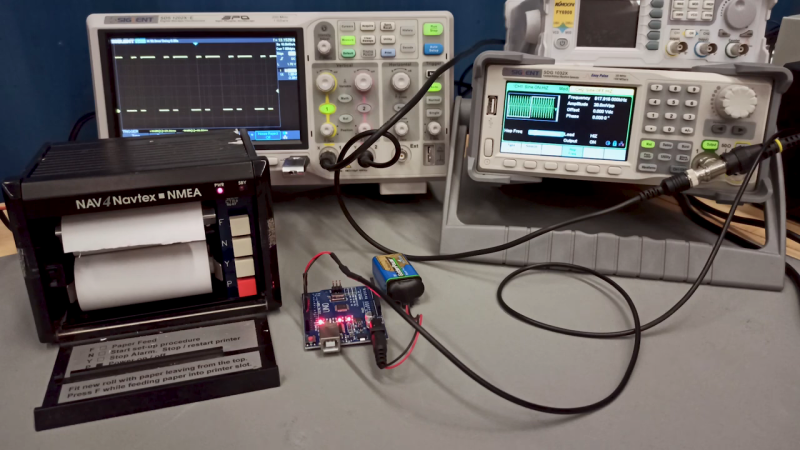

The video does a wonderful job going into the details, but essentially by using an oxygen sensor with finer resolution (wide-band) and then outputting the appropriate narrow band signal to the ECU, [Robot Cantina] can fine tune the air/fuel ratio with nothing more than a potentiometer, and the car’s ECU is none the wiser. What were the results? Well… they weren’t as expected, which means more experimentation, more parts, and hopefully, more videos. We love seeing the scientific method put to fun use!

People are ever in the quest to try interesting new (and sometimes old) ideas, such as this hot rod hacked to run with a lawnmower carburetor.

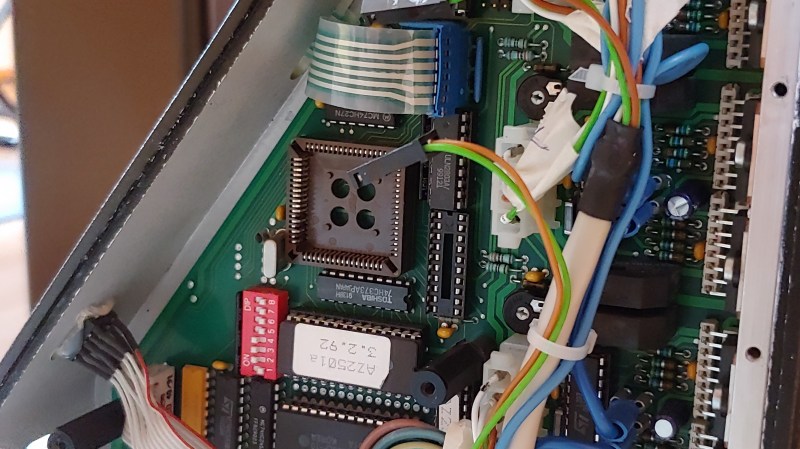

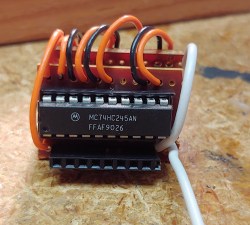

They reverse-engineered the motor driver connections – those go through a 74HC245 buffer between the original CPU and the drivers. Initially, they put an Arduino inside the control box of the CNC and it fit nicely, but it turned out the Arduino’s CPU would restart every time the spindle spun up – apparently, EMC would rear its head. So, they placed the Arduino out of the box, and used two CAT7 cables to wire up the motor and endstop signals to it.

They reverse-engineered the motor driver connections – those go through a 74HC245 buffer between the original CPU and the drivers. Initially, they put an Arduino inside the control box of the CNC and it fit nicely, but it turned out the Arduino’s CPU would restart every time the spindle spun up – apparently, EMC would rear its head. So, they placed the Arduino out of the box, and used two CAT7 cables to wire up the motor and endstop signals to it.