Before Arduino There was Basic Stamp: A Classic Teardown

Microcontrollers existed before the Arduino, and a device that anyone could program and blink an LED existed before the first Maker Faire. This might come as a surprise to some, but for others PICs and 68HC11s will remain as the first popular microcontrollers, found in everything from toys to microwave ovens.

Arduino can’t even claim its prominence as the first user-friendly microcontroller development board. This title goes to the humble Basic Stamp, a four-component board that was introduced in the early 1990s. I recently managed to get my hands on an original Basic Stamp kit. This is the teardown and introduction to the first user friendly microcontroller development boards. Consider it a walk down memory lane, showing us how far the hobbyist electronics market has come in the past twenty year, and also an insight in how far we have left to go.

Teardown

The Basic Stamp kit on my workbench was made in 1993, and sold for a suggested retail price of $139 USD. Adjusted for inflation, this is nearly $230 in 2015 dollars. What do you get in the Basic Stamp starter kit? A single stamp, a programmer cable, and a surprising amount of documentation.

The Basic Stamp is an extremely minimalist board that does just enough to blink an LED, read a button, or drive an LCD. In the official documentation, there are only a handful of parts: a microcontroller, an EEPROM with a few bytes of memory, a crystal, and a voltage regulator.

The PIC16C56XL is the brains of the outfit, featuring 1.5kilobits of Flash memory and 25 bytes of RAM. By modern standards, it’s tiny; the closest modern analog would be the ATtiny10, itself not a very recent chip. Microchip’s smallest and newest chip is the PIC12LF1522, featuring twice as much Flash and ten times the amount of RAM. We’re dealing with an old microcontroller when using the Basic Stamp

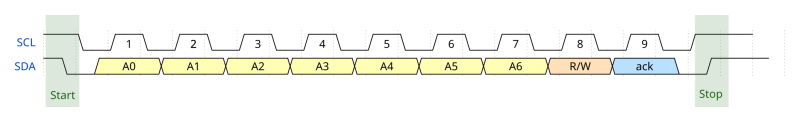

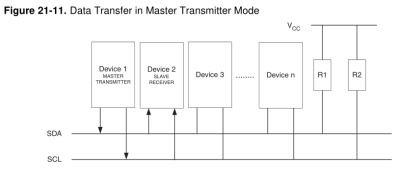

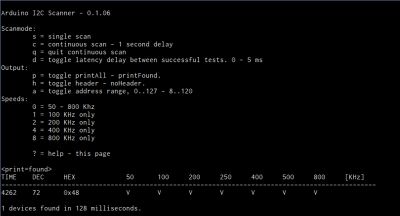

Other components include a 93LC56 serial EEPROM. beside that is a 4MHz regulator, a 5V linear regulator, and a transistor and a few resistors for the ‘brown out’ circuit. Power is provided by a 9V battery connector soldered onto the board.

The electronic design of the Basic Stamp is simple, yes, but there’s a method to the madness. The code you write for the Basic Stamp is stored in 256 bytes of the EEPROM. This code is read by a PBASIC interpreter on the PIC, dutifully following commands to blink a LED or display a character on an LCD. No user code is actually stored on the microcontroller.

Programming

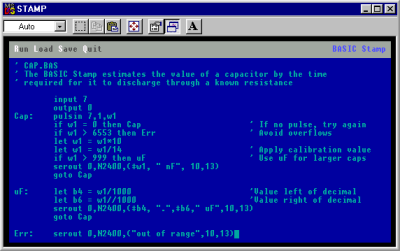

How about the programming environment? That’s a single executable running in a DOS shell. The system requirements are only, an IBM PC or compatible, DOS 2.0+, 128k of RAM, and a disk drive. Meager requirements, but this is not something that will run on your modern Windows workstation; it requires a proper parallel port.

For an IDE, the Basic Stamp editor is comparable to earlier Arduino IDEs; Alt+R runs the program on the Stamp connected to the computer, Alt+L loads a program, Alt+S saves a program, and Alt+Q quits the editor.

The BASIC language implemented on the PIC is minimal, but it does everything you would expect; individual pins can be set as input and output, buttons are debounced, and PWM functions are baked into the language.

Context

The Basic Stamp is now regarded as a slow, inconvenient artifact from the past. No one uses it, and the only place you’ll find one is in the back cabinet in a physics or EE classroom. This is an incredible disservice to a still-impressive piece of technology, and looking back at the Basic Stamp with our modern expectations is an incredible bias.

There were microcontroller development platforms before the Basic Stamp, but these were engineering tools, and expensive compared to the Stamp. Development platforms for the electrical hobbyist were around after the stamp, too: the Micromint Domino packed an entire development platform into a rectangular brick of plastic. None of these designs could match the popularity of the Basic Stamp despite the platform’s shortcomings.

The Arduino receives a lot of hate. Detractors say it’s too high-level for proper embedded programming, not high-level enough for a modern workflow, is based on old, obsolete chips, doesn’t have the features of modern ARM microcontrollers, and the IDE is a mess. Despite an even less capable IDE, meager memory, and a slow processor, the Basic Stamp proved incredibly popular. The fact that you could pick up a Basic Stamp development kit at any Radio Shack probably didn’t hurt it’s popularity, either.

Now, with our fancy IDEs, mbed microcontrollers, powerful ARMs, and huge libraries, the ease of use of the Basic Stamp has still not been equaled. It may be slow, outdated, but all of us owe a great debt to the Basic Stamp for introducing an entire generation to the world of embedded programming, microcontrollers, and electronics tinkering.

Filed under: classic hacks, Featured, Microcontrollers