We’re on a sort of vacation in Tanzania at the moment and staying in a modest hotel away from the tourist and government district. It’s a district of small shops selling the same things and guys repairing washing machines out on the sidewalk. The guys repairing washing machines are more than happy to talk. Everybody’s amazingly friendly here, the hotel guy grilled us for an hour about our home state. But I really didn’t expect to end up in a conversation about computer vision.

In search of some yogurt and maybe something cooler to wear, we went on a little walk away from the hotel. With incredible luck we found a robotics shop a few blocks away. Mecktonix is a shop about two meters each way, stuffed full of Arduinos, robots, electronics components, servos, and random computer gear, overseen by [Yohanna “Joe” Harembo]. Nearby is another space with a laser engraver and 3D printer. The tiny space doesn’t stop them from being busy. A constant stream of automotive tech students from the nearby National Institute of Transport shuffle in for advice and parts for class assigned projects.

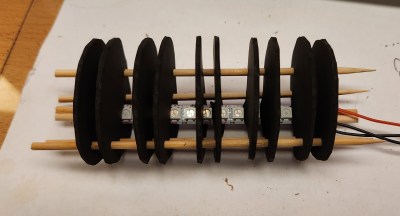

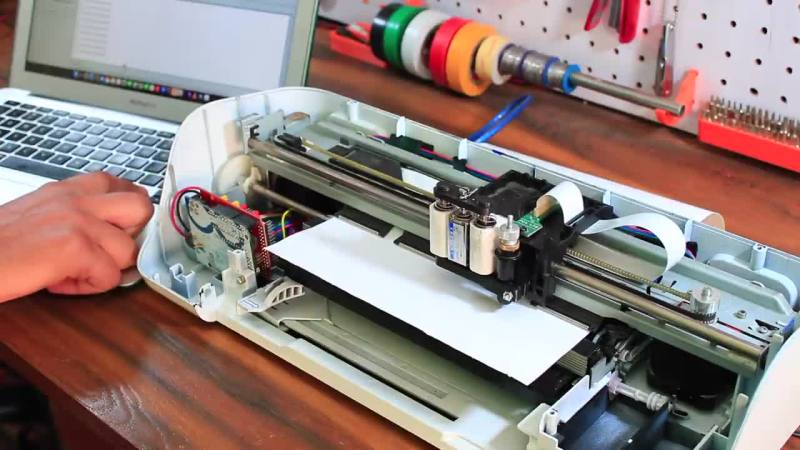

In between students, Joe demos an autonomous car he’s working on. In classic hacker fashion, he first has to reattach the motor driver board and various sensors, but then he demos the car and its problem – the video frame rate is very slow. We dive in with him and try to get some profiling using time.monotonic_ns(). He’s never done profiling before, so this is a big eye opener. He’s only processing one video frame every 4.3 seconds, using YOLO on a Pi 3, and yup, that’s the problem. I suggest he change to gamut detection or a Pi 4.

Gamut Detection

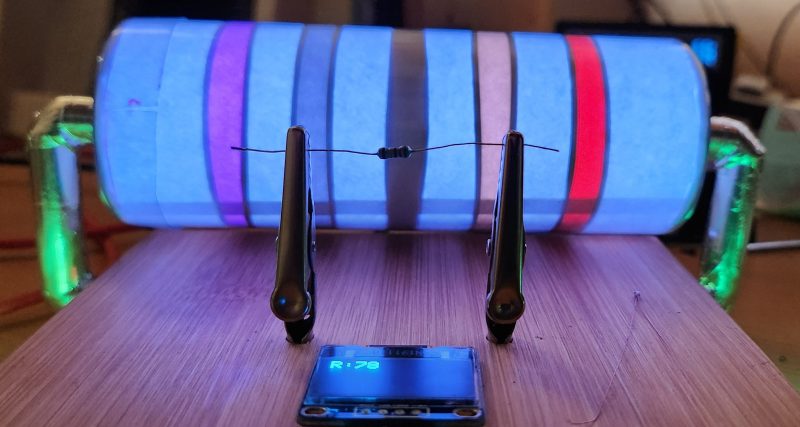

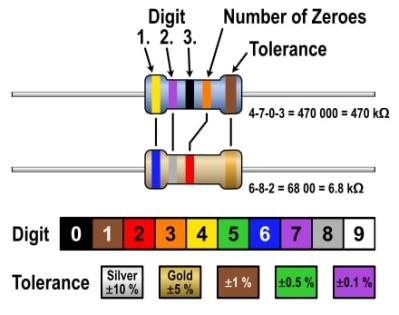

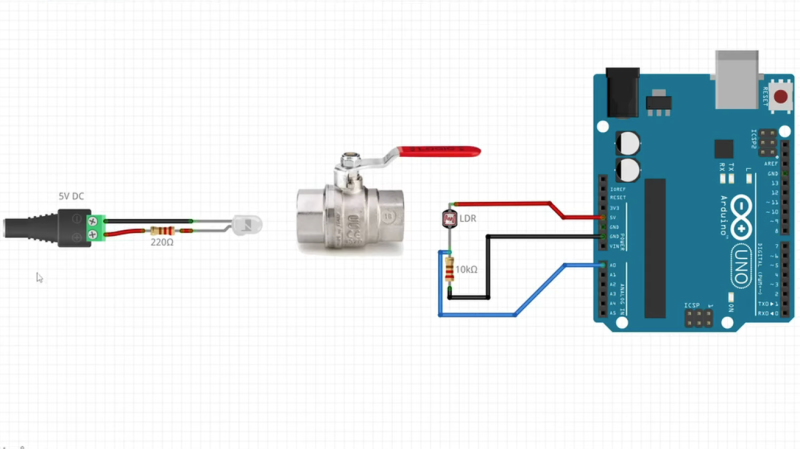

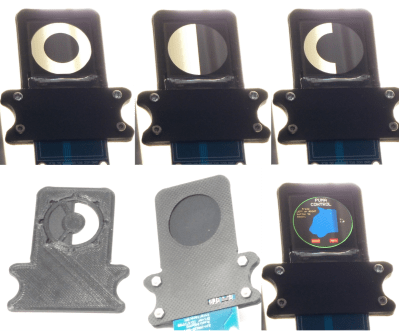

If you’re not familiar with gamut detection, it’s one of the simplest of all computer vision techniques, so it’s easy to implement on slow processors and almost trivial to code. Basically, it’s “look for a color”. If you want your robot to follow you, wear a lime green T shirt. Now the robot just has to look for lime green. Same for catching a ball or following a line. The algorithm is simple – convert each pixel to HSV, where hue corresponds to the direction around the color wheel, saturation corresponds to how concentrated the color is, and value how bright. Brightness depends on the lighting, so you can throw value away and just set limits for H and S. Anything within those limits is part of our target. The box formed by those limits is our “gamut”.

There are a couple speedups you can apply as well. First, ask yourself how much resolution you need from the camera. If you only want to track a green T shirt that’s never less than 24 pixels on screen, turn the resolution down by a factor of six each way and look for four-pixel T shirts. You now have 1/36th as much data to process and your algorithm runs 36 times faster. If you can’t control the camera resolution, you can shrink the image or just sample every nth pixel. Second, you can often ask for a YUV or YIQ image from the camera. Discard Y and set your limits in IQ or UV coordinates. It’s about the same as HSV.

Joe’s eating this up – he’s had limited chances to talk with somebody else who is into computer vision. As we write this, he’s still trying with YOLO, but at lower resolution. If it doesn’t work he’ll try gamut detection. And it’s not his only project. Passenger carrying motorcycles called pikipikis are common here. A student has a project to enforce passengers wearing a helmet, and we fiddle with the student’s project.

The Dar es Salaam Scene

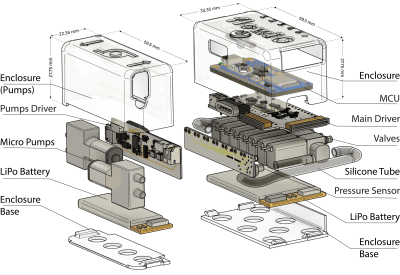

There’s other tech happening in Tanzania too. A few blocks away is [Ruta Electronics], a similar sugar cube sized shop developing smart meters. Everything from cases to PCB etching happens in the tiny shop. Downtown there are a few tech startups. There’s a fab lab, mostly oriented towards children. And on a quiet side street off the main drag, there’s a tiny shop with three guys who are hacking like crazy.

For us, we’ve had a chance to make a friend from a different culture and play with a robot car together — what could be better? When you’re traveling, are you on the lookout for other hackers or hackerspaces? It’s worth the effort and brings our community together in a way that even the internet can’t.