Captivating Clock Puts Endangered Displays On Display

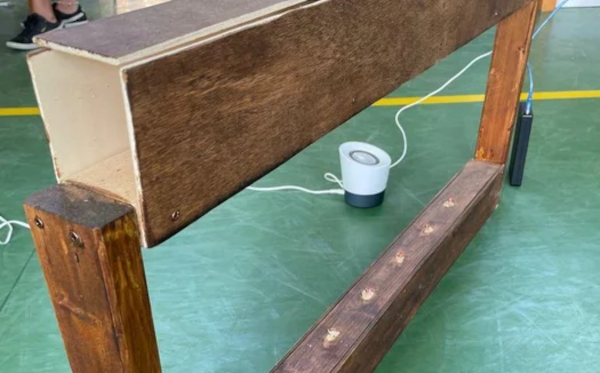

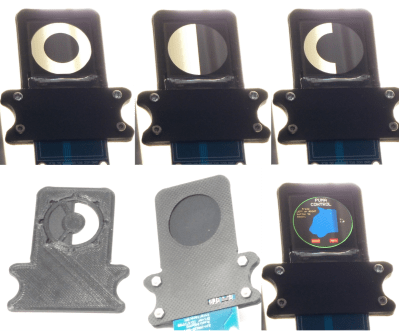

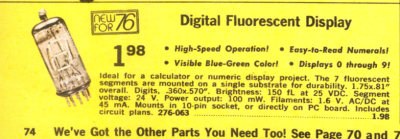

When you have a small stock of vacuum fluorescent displays (VFDs) straight out of the 1976 Radio Shack catalog, you might sit around wondering what to do with them. When [stepawayfromthegirls] found out that his stash of seven DT-1704A tubes may be the last in existence, there was no question. They must be displayed! [stepawayfromthegirls]’ mode of display is this captivating clock build. Four VFDs with their aqua colored elements are set against a black background in a bespoke wooden case. Looking under the hood, the beauty only increases.

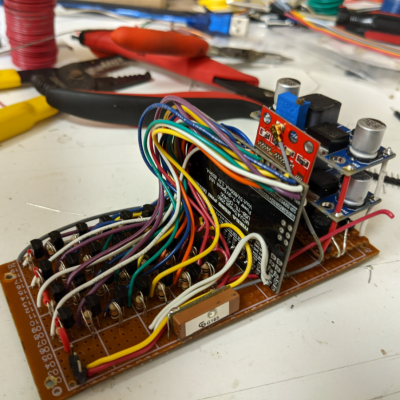

Keeping the build organized was not an easy task because the tubes are designed in such a way that each segment must be individually controlled. The needed I/O duties are provided by an Arduino Mega 2560 Pro (Embed). 28 2n3904’s each with their two resistors serve as drivers for each VFD segment.

The output of a 24 V AC transformer left over from the 1980s is rectified to 34 V of DC power which is then regulated to 27 V to power the tubes. Switching power supplies provide 6 V to the Arduino and 1.3 V to the filaments. If you look closely, you’ll also see a GPS module so that the clock doesn’t need to be set. To future-proof the clock against daylight savings time adjustments, a potentiometer on the back of the case allows the user to set custom hour offsets without editing any code.

We think the end result is a remarkably clean, simple, and elegant clock that he will be proud of for many years to come!

If VFD clock builds are your thing, then you’ll enjoy this Network Attached VFD Clock and a Mini VFD Clock with floating display. And while not VFD based, we’d be silly to leave out the Boat Anchor Nixie Clock with enough knobs, switches, and buttons to delight even the fussiest of hacker.