One Of The Worst Keyboards Ever, Now An Arduino Peripheral

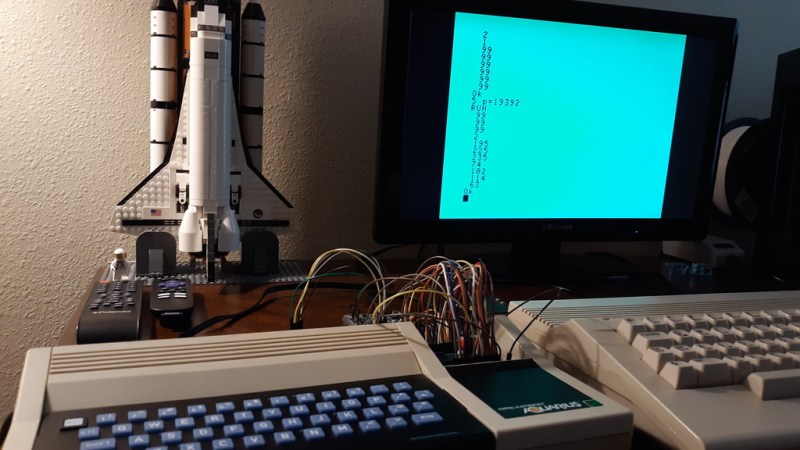

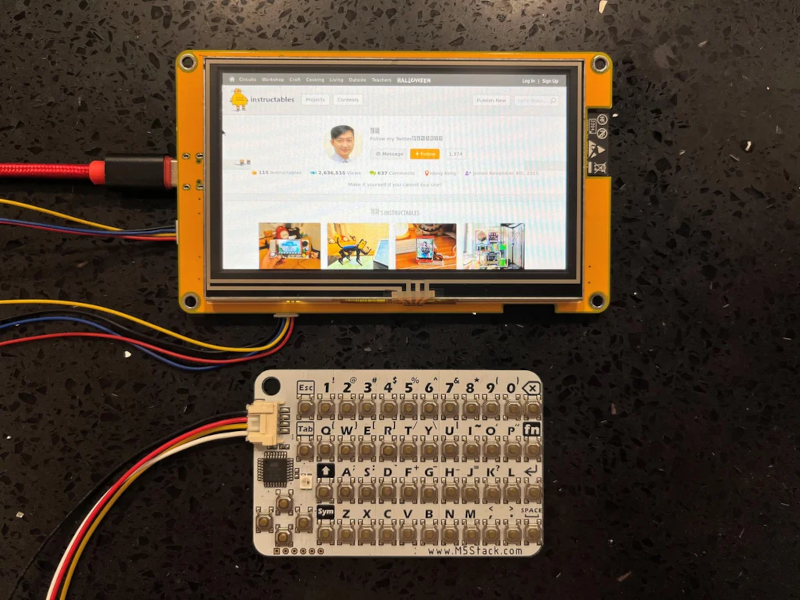

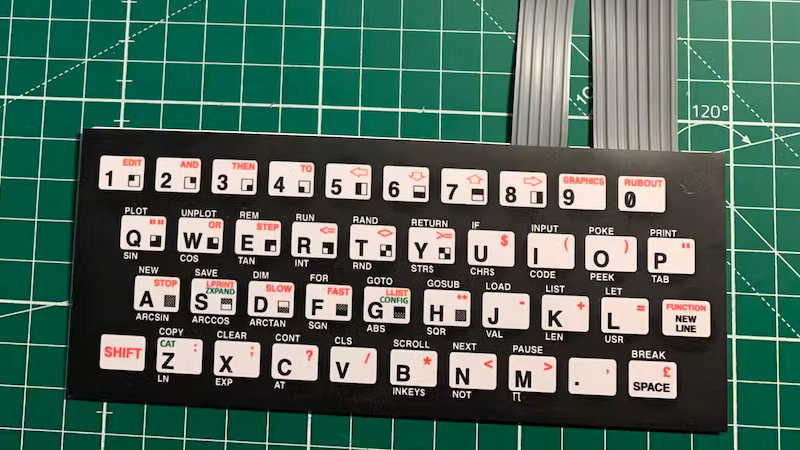

For British kids of a certain age, their first experience of a computer was very likely to have been in front of a Sinclair ZX81. The lesser-known predecessor to the wildly-successful ZX Spectrum, it came in at under £100 and sported a Z80 processor and a whopping 1k of memory. In the long tradition of Sinclair products it had a few compromises to achieve that price point, the most obvious of which was a 40-key membrane keyboard. Those who learned to code on its frustrating lack of tactile feedback may be surprised to see an Arduino project presenting it as the perfect way to easily hook up a keyboard to an Arduino.

Like many retrocomputing parts, the ZX81 ‘board has been re-manufactured, to the joy of many a Sinclair enthusiast. It’s thus readily available and relatively cheap (we think they can be found for less than the stated 20 euros!), so surprisingly it’s a reasonable choice for an Arduino project. The task of trying to define by touch the imperceptible difference in thickness of a ZX81 key will bring a true retrocomputing experience to a new generation. Perhaps if it can be done on an Mbed then someone might even make a ZX81 emulator on the Arduino.

We’re great fans of the ZX81 here at Hackaday, for some of us it was that first computer. Long may it continue to delight its fans!