I’ve always appreciated simulation tools. Sure, there’s no substitute for actually building a circuit but it sure is handy if you can fix a lot of easy problems before you start soldering and making PCBs. I’ve done quite a few posts on LTSpice and I’m also a big fan of the Falstad simulator in the browser. However, both of those don’t do a lot for you if a microcontroller is a major part of your design. I recently found an open source project called Simulide that has a few issues but does a credible job of mixed simulation. It allows you to simulate analog circuits, LCDs, stepper and servo motors and can include programmable PIC or AVR (including Arduino) processors in your simulation.

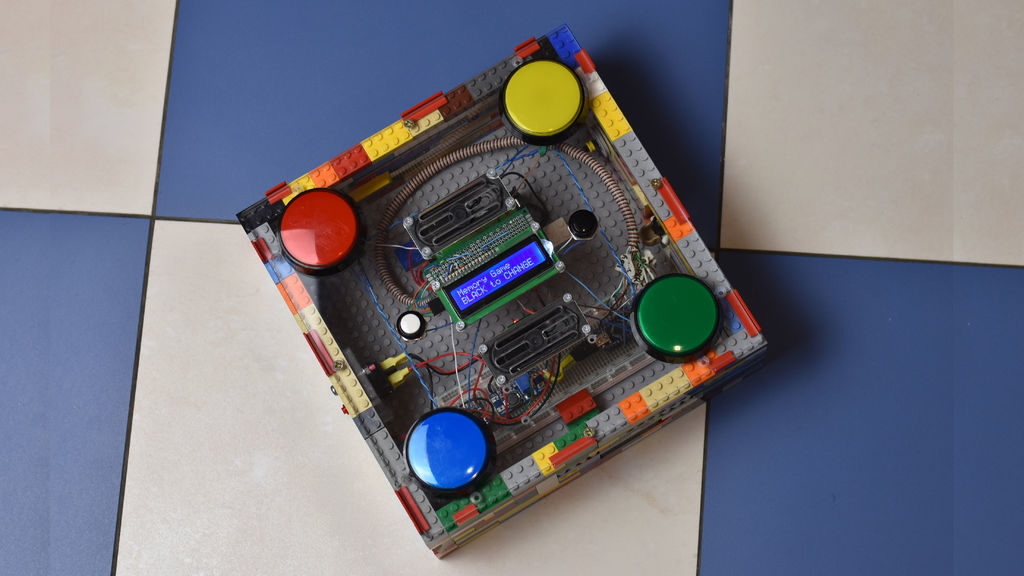

The software is available for Windows or Linux and the AVR/Arduino emulation is built in. For the PIC on Linux, you need an external software simulator that you can easily install. This is provided with the Windows version. You can see one of several videos available about an older release of the tool below. There is also a window that can compile your Arduino code and even debug it, although that almost always crashed for me after a few minutes of working. As you can see in the image above, though, it is capable of running some pretty serious Arduino code as long as you aren’t debugging.

Looks and sounds exciting, right? It is, but be sure to save often. Under Linux, it seems to crash pretty frequently even if you aren’t debugging. It also suffers from other minor issues like sometimes forgetting how to move components. Saving, closing the application, and reopening it seems to fix that. Plus, we assume they will squash bugs as they are reported. One of my major hangs was solved by removing the default (old) Arduino IDE and making sure the most recent was on the path. But the crashing was frequent and seemed more or less random. It seemed that I most often had crashes on Linux with occasional freezes but on Windows it would freeze but not totally crash.

Basic Operation

The basic operation is pretty much what you’d expect. The window is broadly divided into three panes. The leftmost pane shows, by default, a palette of components. You can use the vertical tab strip on the left to also pick a memory viewer, a property inspector, or a file explorer.

The central pane is where you can draw your circuit and it looks like a yellow piece of engineering paper with a grid. Along the top are file buttons that do things like save and load files.

You’ll see a similar row of buttons above the rightmost pane. This is a code editor and debugging window that can interface with the Arduino IDE. It looks like it can also interface with GCBasic for the PIC, although I didn’t try that.

You drag components from the left onto the circuit. Wiring isn’t a distinct operation. You just let the mouse float over the connection until the cursor makes a cross. Click and then drag to the connection point and click again. Sometimes the program forgets to make the cross cursor and then I’ve had to save and restart.

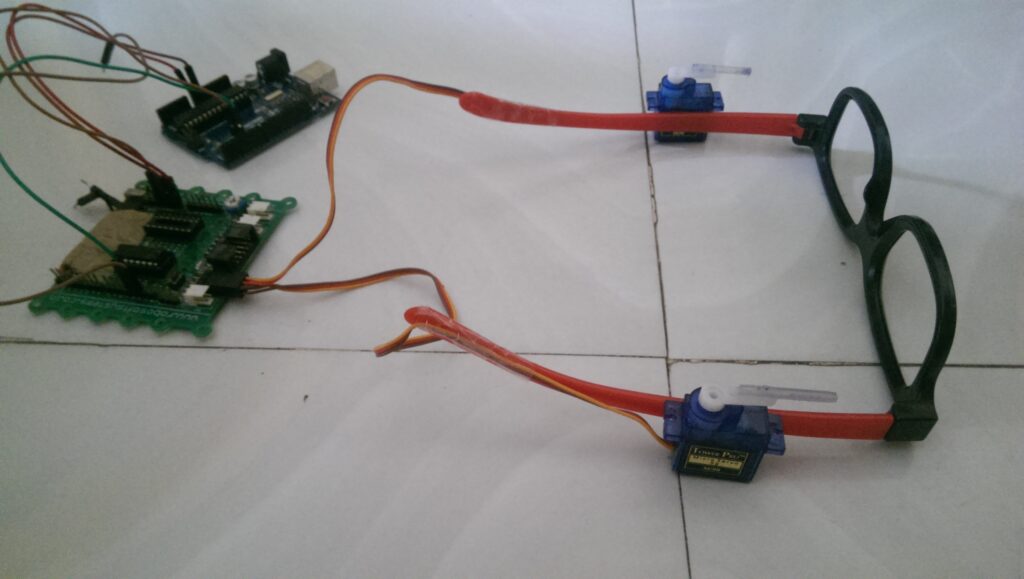

Most of the components are just what you think they are. There are some fun ones including a keypad, an LED matrix, text and graphic LCDs, and even stepper and servo motors. You’ll also find several logic functions, 7400-series ICs, and there are annotation tools like text and boxes at the very bottom. You can right click on a category and hide components you never want to see.

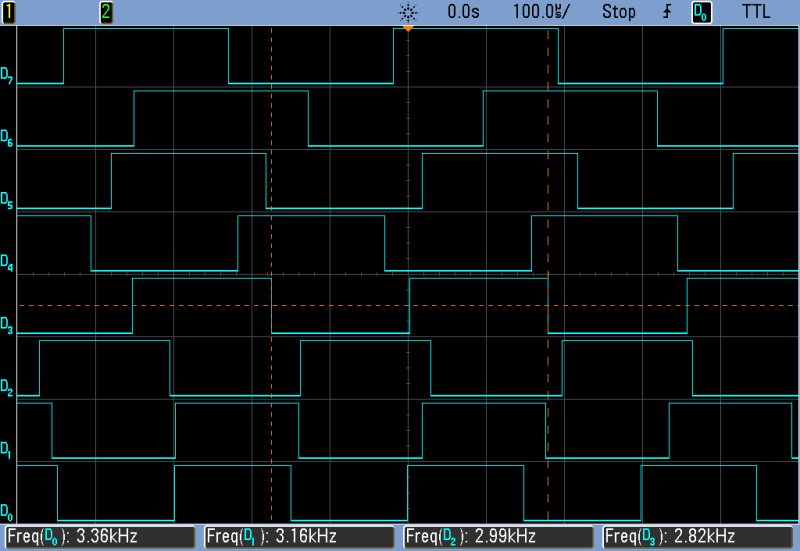

At the top, you can add a voltmeter, an ammeter, or an oscilloscope to your circuit. The oscilloscope isn’t that useful because it is small. What you really want to do is use a probe. This just shows the voltage at some point but you can right click on it and add the probe to the plotter which appears at the bottom of the screen. This is a much more useful scope option.

There are a few quirks with the components. The voltage source has a push button that defaults to off. You have to remember to turn it on or things won’t work well. The potentiometers were particularly frustrating. The videos of older versions show a nice little potentiometer knob and that appears on my Windows laptop, too. On Linux the potentiometer (and the oscilloscope controls) look like a little tiny joystick and it is very difficult to set a value. It is easier to right click and select properties and adjust the value there. Just note that the value won’t change until you leave the field.

There are a few quirks with the components. The voltage source has a push button that defaults to off. You have to remember to turn it on or things won’t work well. The potentiometers were particularly frustrating. The videos of older versions show a nice little potentiometer knob and that appears on my Windows laptop, too. On Linux the potentiometer (and the oscilloscope controls) look like a little tiny joystick and it is very difficult to set a value. It is easier to right click and select properties and adjust the value there. Just note that the value won’t change until you leave the field.

Microcontroller Features

If that’s all there was to it, you’d be better off using any of a number of simulators that we’ve talked about before. But the big draw here is being able to plop a microcontroller down in your circuit. The system provides PIC and AVR CPUs that are supported by the simulator code it uses. There’s also four variants of Arduinos: the Uno, Nano, Duemilanove, and the Leonardo.

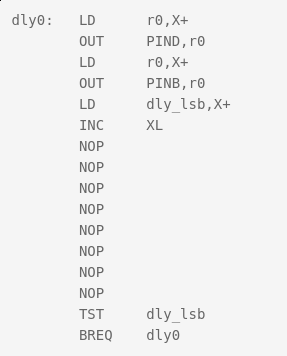

You can use the built-in Arduino IDE — just make sure you have the real Arduino software on your path and it is a recent version. Also, unlike the real IDE, it appears you must save your file before a download or debug will notice the changes. In other words, if you make a change and download, you’ll compile the code before the change if you didn’t save the file first. You don’t have to use the built-in IDE. You can simply right click on the processor and upload a hex file. Recent Arduino IDEs have an option to export a hex file, and that works with no problem.

When you have a CPU in your design, you can right click it and open a serial monitor port which shows virtual serial output at the bottom of the screen and lets you provide input.

The debugging mode is simple but works until it crashes. Even without debugging, there is an option to the left of the screen to watch memory locations and registers inside the CPU.

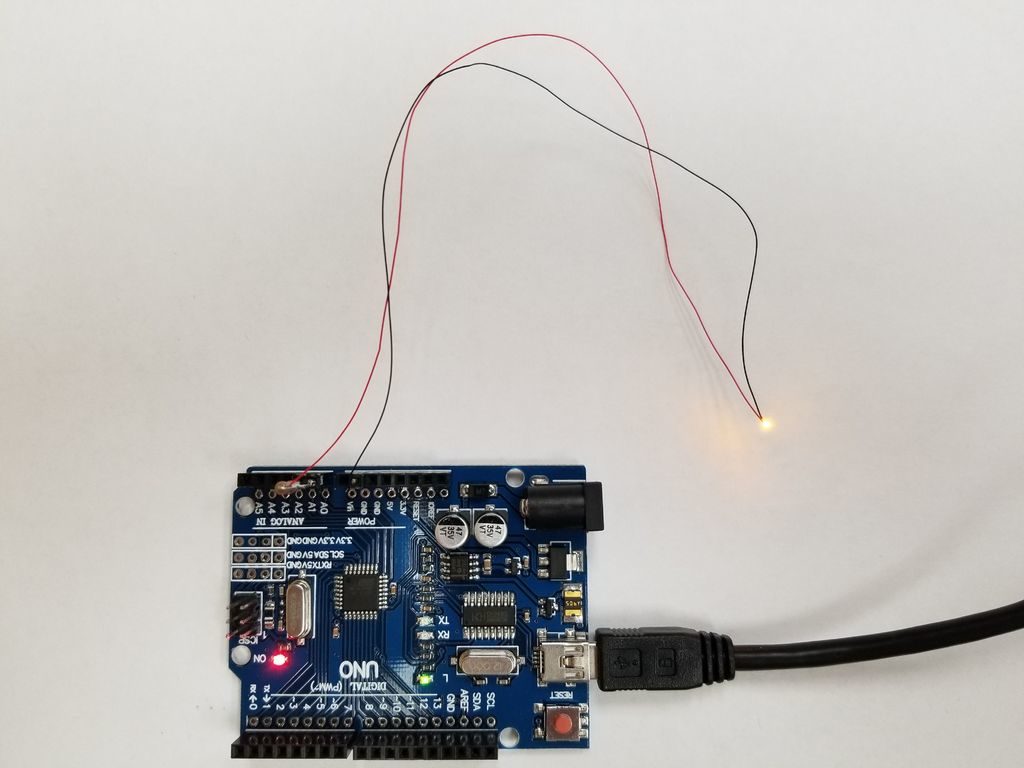

Overall, the Arduino simulation seemed to work quite well. Connecting to the Uno pins was a little challenging at certain scales and I accidentally wired to the wrong pin on more than one occasion. One thing I found odd is that you don’t need to wire the voltage to the Arduino. It is powered on even if you don’t connect it.

Besides the crashing, the other issue I had was with the simulation speed which was rather slow. There’s a meter at the top of the screen that shows how slow the simulation is compared to real-time and mine was very low (10% or so) most of the time. There is a help topic explaining that this depends if you have certain circuit elements and ways to improve the run time, but it wasn’t bad enough that I bothered to explore it.

My first thought was that it would be difficult to handle a circuit with multiple CPUs in it since the debugging and serial monitors are all set up for a single CPU. However, as the video below shows, you can run multiple instances of the program and connect them via a serial port connection. The only issue would be if you had a circuit where both CPUs were interfacing with interrelated circuitry (for example, an op amp summing two signals, one from each CPU).

A Simple Example

As an experiment, I created a simple circuit that uses an Uno. It generates two PWM signals, integrates them with an RC circuit and then either drives a load or drives a load through a bipolar emitter follower. A pot lets you set the PWM percentages which are compliments of each other (that is, when one is at 10% the other is at 90%). Here’s the circuit:

Along with the very simple code:

int v;

const int potpin=0;

const int led0=5;

const int led1=6;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.println("Here we go!");

}

void loop() {

int v=analogRead(potpin)/4;

Serial.println(v);

analogWrite(led0,v);

analogWrite(led1,255-v);

delay(250);

}

Note that if the PWM output driving the transistor drops below 0.7V or so, the transistor will shut off. I deliberately didn’t design around that because I wanted to see how the simulator would react. It correctly models this behavior.

There’s really no point to this other than I wanted something that would work out the analog circuit simulation as well as the Arduino. You can download all the files from GitHub, including the hex file if you want to skip the compile step.

If you use the built-in IDE on the right side of the screen, then things are very simple. You just download your code. If you build your own hex file, just right click on the Arduino and you’ll find an option to load a hex file. It appears to remember the hex file, so if you run a simulation again later, you don’t have to repeat that step unless you moved the hex file.

However, the IDE doesn’t remember settings for the plotter, the voltage switches, or the serial terminal. You’ll especially want to be sure the 5V power switch above the transistor is on or that part of the circuit won’t operate correctly. You can right click on the Arduino to open the serial monitor and right click on the probes to bring back the plotter pane.

The red power switch at the top of the window will start your simulation. The screenshots above show close-ups of the plot pane and serial monitor.

Lessons Learned

This could be a really great tool if it would not crash so much. In all fairness, that could have something to do with my PC, but I don’t think that fully accounts for all of them. However, the software is still in pretty early development, so perhaps it will get better. There are a lot of fit and finish problems, too. For example, on my large monitor, many of the fonts were too large for their containers, which isn’t all that unusual.

The user interface seemed a little clunky, especially when you had to manipulate potentiometers and switches. Also, remember you can’t right-click on the controls but must click on the underlying component. In other words, the pot looks like a knob on top of a resistor. Right clicks need to go on the resistor part, not the knob. I also was a little put off that you can’t enter multiplier suffixes directly in component values. That is, you can’t enter a resistor value as 1K. You can enter 1000 or you can enter 1 and then change the units in a separate field to Kohms. But that’s not a big deal. You can get used to all of that if it would quit crashing.

I really wanted the debugging feature to work. While you can debug directly with simuavr or other tools, you can’t easily simulate all your I/O devices like you can with this tool. I’m hoping that becomes more robust in the future. Under Linux it would work for a bit and crash. On Windows, I never got it to work.

As I always say, though, simulation is great, but the real world often leads to surprises that don’t show up in simulation. Still, a simulation can help you clear up a host of problems before you commit to heating up the soldering iron or pulling out the breadboard. Simuide has the potential to be a great tool for simulating the kind of designs we see most on Hackaday.

If you want to explore other simulation options, we’ve talked a lot about LTSpice, including our Circuit VR series. There’s also the excellent browser-based Falstad simulator.