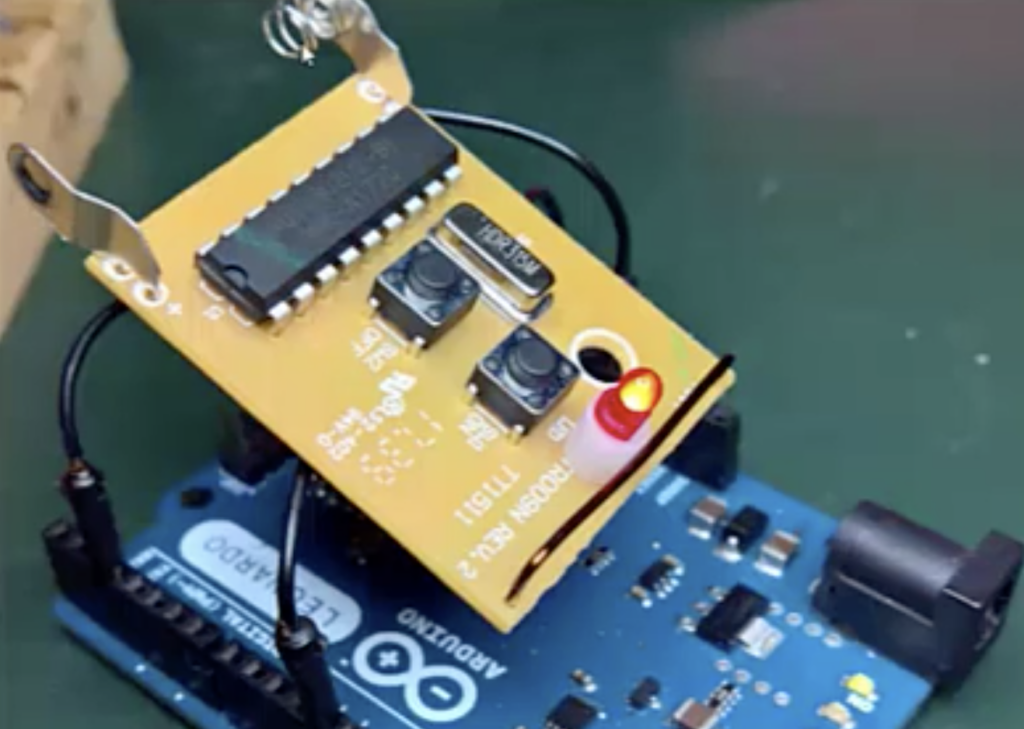

Certain hobbies come in clusters. It isn’t uncommon to see, for example, ham radio operators that are private pilots. Programmers who are musicians. Electronics people who build model trains. This last seems like a great fit since you can do lots of interesting things with simple electronics and small-scale trains. [Jimmy] at the aptly-named DIY and Digital Railroad channel has several videos on integrating railroad setups with Arduino. These range from building a DCC system for about $45 (see below) to a crossing signal.

There are actually quite a few basic Arduino videos on the channel, although most of them are aimed at beginners. However, the DCC — Digital Command and Control — might be new to you if you are a train neophyte. DCC is a standard defined by the National Model Railroad Association.

Model trains pick up electrical power from the rails. DCC allows digital messages to also ride the rail. The signal shifts from positive to negative to indicate marks and spaces. By diode switching the electrical signal, the train or other equipment can get a constant supply of current. However, equipment monitoring the line ahead of the diodes can read the data and interpret it as commands.

To accommodate old equipment, you can stretch the high or low values to make the average voltage either positive (forward) or negative (reverse). This can heat up DC motors, though, so it may shorten the life of the legacy equipment.

The build uses an available Arduino library, so if you want to get into the protocol you’ll have to work through that code. We had to wonder if there were other places where passing power and data on the same lines might be useful. There are other ways to do that, of course, but this would be a reasonable place to start if you needed that capability.

If you want to use an mBed system instead of an Arduino, there’s a great tutorial for that. Either way, it is just the thing for your next coffee table.