Connect your Arduino Mega or compatible to the cellular network with the SM5100 GSM module shield from Tronixlabs. If you have an Arduino Uno or compatible, visit this page. If you are looking for tutorials using the SIMCOM SIM900 GSM module, click here.

This is chapter twenty-seven of a series originally titled “Getting Started/Moving Forward with Arduino!” by John Boxall – A tutorial on the Arduino universe. The first chapter is here, the complete series is detailed here.

Updated 18/01/2014

Introduction

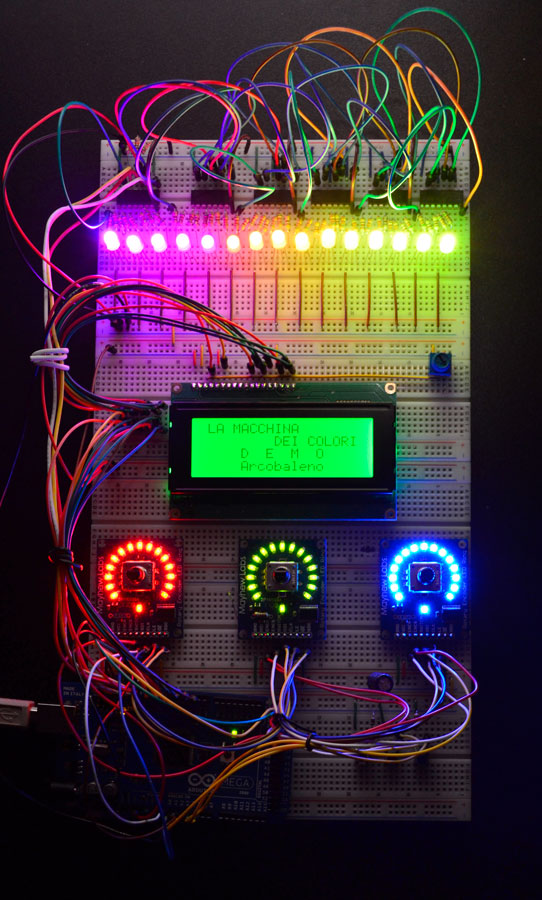

The purpose of this tutorial is to have your Arduino Mega to communicate over a GSM mobile telephone network using a shield based on the SM5100B module from Tronixlabs. We’ve written this as the shield from Sparkfun used in the previous tutorial was somewhat fiddly for use with an Arduino Mega – so this shield is a more convenient alternative:

Our goal is to illustrate various methods of interaction between an Arduino Mega and the GSM cellular network using the shield shown above, with which you can then use your existing knowledge to build upon those methods. Doing so isn’t easy – but it isn’t that difficult.

Stop! Please read first:

- It is assumed that you have a solid understanding of how to program your Arduino. If not, start from chapter zero

- Sending SMS messages and making phone calls cost real money, so it would be very wise to use a prepaid cellular account or one that allows a fair amount of calls/SMS

- The GSM shield only works with “2G” GSM mobile networks operating on the 850, 900 and PCS1800 MHz frequencies. If in doubt, ask your carrier first

- Australians – you can use any carrier’s SIM card

- Canadians – this doesn’t work with Sasktel

- North Americans – check with your cellular carrier first if you can use third-party hardware (i.e. the shield)

- I cannot offer design advice for your project nor technical support for this article.

- If you are working on a college/university project and need specific help – talk to your tutors or academic staff. They get paid to help you.

- Please don’t make an auto-dialler…

Getting started

Before moving forward there us one vital point you need to understand – the power supply. The GSM shield can often require up to 2A of current in short bursts – especially when turned on, reset, or initiating a call.

However your Arduino board can only supply just under 1A. It is highly recommended that you use an external regulated power supply of between 9 and 12 VDC capable of delivering 2A of current – from an AC adaptor, large battery with power regulator, etc. Otherwise there is a very strong probability of damaging your shield and Arduino. When connecting this supply use the Vin and GND pins. Do not under any circumstances power the Arduino and shield from just the USB power.

Next – use an antenna! The wire hanging from the shield is not an antenna. YOU NEED THE ANTENNA! For example:

Furthermore, care needs to be taken with your GSM shield with regards to the aerial lead-module connection, it is very fragile:

Pressing the hardware reset button on the shield doesn’t reset the GSM module – you need to remove the power for a second. And finally, download this document (.pdf). It contains all the AT and ERROR codes that will turn up when you least expect it. Please review it if you are presented with a code you are unsure about.

Wow – all those rules and warnings?

The sections above may sound a little authoritarian, however I want your project to be a success. With the previous iterations of the tutorial people just didn’t follow the instructions – so we hope you do.

Initial check – does it work?

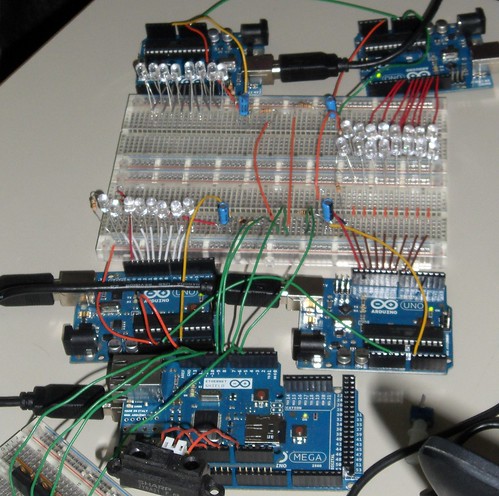

This may sound like a silly question, but considering the cost of the shield and the variables involved, it is a good idea to check if your setup is functioning correctly before moving on. From a hardware perspective for this article, you will need your Arduino board, the GSM shield with activated SIM card and an aerial, and the power supply connected.

Next you need to set the serial line jumpers. These determine which of the four hardware serial ports we use to communicate with the GSM module. Place a jumper over each of the RX1 and TX1 pairs as shown in the following image. By doing this the communication with the GSM module is via Serial1 in our sketches, leaving Serial for normal communications such as the serial monitor.

Make sure your SIM card is set to not require a PIN when the phone is turned on. You can check and turn this requirement off with your cellphone.

For our initial test, upload the following sketch:

// Example 27.1

char incoming_char=0; // Will hold the incoming character from the Serial Port.

void setup()

{

//Initialize serial ports for communication.

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial1.begin(9600);

Serial.println("Starting SM5100B Communication...");

}

void loop()

{

//If a character comes in from the cellular module...

if(Serial1.available() >0)

{

incoming_char=Serial1.read(); // Get the character from the cellular serial port.

Serial.print(incoming_char); // Print the incoming character to the terminal.

}

//If a character is coming from the terminal to the Arduino...

if(Serial.available() >0)

{

incoming_char=Serial.read(); // Get the character coming from the terminal

Serial1.print(incoming_char); // Send the character to the cellular module.

}

}Then connect the GSM shield, aerial, insert the SIM card and apply power. Open the serial monitor box in the Arduino IDE and you should be presented with the following:

It will take around fifteen to thirty seconds for the text above to appear in full. What you are being presented with is a log of the GSM module’s actions. But what do they all mean?

- +SIND: 1 means the SIM card has been inserted;

- the +SIND: 10 line shows the status of the in-module phone book. Nothing to worry about there for us at the moment;

- +SIND: 11 means the module has registered with the cellular network

- +SIND: 3 means the module is partially ready to communicate

- and +SIND: 4 means the module is registered on the network, and ready to communicate

All the SIND data and other codes the module will give you are listed in the AT command guide we suggested you download. Please use it – any comments such as “What’s +SIND:5?” will be deleted.

From this point on, we will need to use a different terminal program, as the Arduino IDE’s serial monitor box isn’t made for full two-way communications. You will need a terminal program that can offer full two-way com port/serial communication. For those running MS Windows, an excellent option is available here.

It’s free, however consider donating for the use of it. For other operating systems, people say this works well. So now let’s try it out with the terminal software. Close your Arduino IDE serial monitor box if still open, then run your terminal, set it to look at the same serial port as the Arduino IDE was. Ensure the settings are 9600, 8, N, 1. Then reset your Arduino and the following should appear:

The next step is to tell the GSM module which network frequency(ies) to use. View page 127 of the AT command document. There is a range of frequency choices that our module can use. If you don’t know which one to use, contact the telephone company that your SIM card came from. Australia – use option 4. Find your option, then enter:

AT+SBAND=x

(where X is the value matching your required frequency) into the terminal software and click SEND. Then press reset on the Arduino and watch the terminal display. You should hopefully be presented with the same text as above, ending with +SIND: 4. If your module returns +SIND: 4, we’re ready to move forward.

If your terminal returned a +SIND: 8 instead of 4, double-check your hardware, power supply, antenna, and the frequency band chosen. If all that checks out call your network provider to see if they’re rejecting the GSM module on their network.

Our next test is to call our shield. So, pick up a phone and call it. Your shield will return data to the terminal window, for example:

As you can see, the module returns what is happening. I let the originating phone “ring” three times, and the module received the caller ID data (sorry, blacked it out). Some telephone subscribers’ accounts don’t send caller ID data, so if you don’t see your number, no problem. “NO CARRIER” occurred when I ended the call. +SIND: 6,1 means the call ended and the SIM is ready.

Have your Arduino “call you”

The document (.pdf) you downloaded earlier contains a list of AT commands – consider this a guide to the language with which we instruct the GSM module to do things. Let’s try out some more commands before completing our initial test. The first one is:

ATDxxxxxx

which dials a telephone number xxxxxx. For example, to call (212)-8675309 use:

ATD2128675309

The next one is:

ATH

which “hangs up” or ends the call. So, let’s reach out and touch someone. In the terminal software, enter your ATDxxxxxxxx command, then hit send. Let your phone ring. Then enter ATH to end the call. If you are experimenting and want to hang up in a hurry, you can also hit reset on the Arduino and it will end the call as well as resetting the system.

So by now you should realise the GSM module is controlled by these AT commands. To use an AT command in a sketch, we use the function:

Serial1.println()

Remember that we used Serial1 as the jumpers on the shield board are set to connect the GSM module to the Serial1 hardware serial port. For example, to dial a phone number, we would use:

Serial1.println("ATD2128675309");To demonstrate this in a sketch, consider the following simple sketch which dials a telephone number, waits, then hangs up. Replace xxxxxxxx with the number you wish to call:

// Example 27.2

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial1.begin(9600);

delay(10);

Serial.println("starting delay");

delay(30000); // give the GSM module time to initialise, locate network etc.

// this delay time varies. Use example 27.1 sketch to measure the amount

// of time from board reset to SIND: 4, then add five seconds just in case

}

void loop()

{

Serial.println("dialling");

Serial1.println("ATDxxxxxxxxxx"); // dial the phone number xxxxxxxxx

// change xxxxxxxxxx to your desired phone number (with area code)

delay(20000); // wait 20 seconds.

Serial.println("hang up");

Serial1.println("ATH"); // end call

do // remove this loop at your peril

{

delay(1);

}

while (1>0);

}The sketch in example 27.2 assumes that all is well with regards to the GSM module, that is the SIM card is ok, there is reception, etc. The long delay function in void setup() is used to allow time for the module to wake up and get connected to the network. Later on we will read the messages from the GSM module to allow our sketches to deal with errors and so on. However, you can see how we can simply dial a telephone. And here’s a quick video for the non-believers.

Send an SMS from your Arduino

Another popular function is the SMS or short message service, or text messaging. Before moving forward, download and install Meir Michanie’s SerialGSM Arduino library from here. Some of you might be thinking “why are we using a software serial in the following sketch?”. Short answer – it’s just easier.

Sending a text message is incredibly simple – consider the following sketch:

// Example 27.3

#include <SerialGSM.h>

#include <SoftwareSerial.h>

SerialGSM cell(19,18);

void setup()

{

delay(30000); // wait for GSM module

cell.begin(9600);

}

void sendSMS()

{

cell.Verbose(true); // used for debugging

cell.Boot();

cell.FwdSMS2Serial();

cell.Rcpt("+xxxxxxxxx"); // replace xxxxxxxxx with the recipient's cellular number

cell.Message("Contents of your text message");

cell.SendSMS();

}

void loop()

{

sendSMS();

do // remove this loop at your peril

{

delay(1);

}

while (1>0);

}It’s super-simple – just change the phone number to send the text message, and of course the message you want to send. The phone numbers must be in international format, e.g. Australia 0418 123456 is +61418123456 or USA (609) 8675309 is +16098675309. And the results:

Reach out and control something

Now let’s discuss how to make something happen by a simple telephone call. And the best thing is that we don’t need the the GSM module to answer the telephone call (thereby saving money) – just let the module ring a few times. How is this possible? Very easily. Recall Example 27.1 above – we monitored the activity of the GSM module by using our terminal software.

In this case what we need to do is have our Arduino examine the text coming in from the serial output of the GSM module, and look for a particular string of characters.

When we telephone the GSM module from another number, the module returns the text as shown in the image below:

We want to look for the text “RING”, as (obviously) this means that the GSM shield has recognised the ring signal from the exchange. Therefore need our Arduino to count the number of rings for the particular telephone call being made to the module. (Memories – Many years ago we would use public telephones to send messages to each other.

For example, after arriving at a foreign destination we would call home and let the phone ring five times then hang up – which meant we had arrived safely). Finally, once the GSM shield has received a set number of rings, we want the Arduino to do something.

From a software perspective, we need to examine each character as it is returned from the GSM shield. Once an “R” is received, we examine the next character. If it is an “I”, we examine the next character. If it is an “N”, we examine the next character. If it is a “G”, we know an inbound call is being attempted, and one ring has occurred.

We can set the number of rings to wait until out desired function is called. In the following example, when the shield is called, it will call the function doSomething() after three rings.

The function doSomething() controls two LEDs, two red, two green. Every time the GSM module is called for 3 rings, the Arduino alternately turns on or off the LEDs. Using the following sketch as an example, you now have the ability to turn basically anything on or off, or call your own particular function:

// Example 27.4

char inchar; // Will hold the incoming character from the Serial Port.

int numring=0;

int comring=3;

int onoff=0; // 0 = off, 1 = on

int led1 = 9;

int led2 = 10;

int led3 = 11;

int led4 = 12;

void setup()

{

// prepare the digital output pins

pinMode(led1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led4, OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(led1, LOW);

digitalWrite(led2, LOW);

digitalWrite(led3, LOW);

digitalWrite(led4, LOW);

//Initialize GSM module serial port for communication.

Serial1.begin(9600);

delay(30000); // give time for GSM module to register on network etc.

}

void doSomething()

{

if (onoff==0)

{

onoff=1;

digitalWrite(led1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(led2, HIGH);

digitalWrite(led3, LOW);

digitalWrite(led4, LOW);

}

else

if (onoff==1)

{

onoff=0;

digitalWrite(led1, LOW);

digitalWrite(led2, LOW);

digitalWrite(led3, HIGH);

digitalWrite(led4, HIGH);

}

}

void loop()

{

//If a character comes in from the cellular module...

if(Serial1.available() >0)

{

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='R')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='I')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='N')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='G')

{

delay(10);

// So the phone (our GSM shield) has 'rung' once, i.e. if it were a real phone

// it would have sounded 'ring-ring'

numring++;

if (numring==comring)

{

numring=0; // reset ring counter

doSomething();

}

}

}

}

}

}

}And now for a quick video demonstration. Each time a call to the shield is made, the pairs of LEDs alternate between on and off. Although this may seem like an over-simplified example, with your existing Arduino knowledge you now have the ability to run any function by calling your GSM shield.

Control Digital I/O via SMS

Now although turning one thing on or off is convenient, how can we send more control information to our GSM module? For example, control four or more digital outputs at once? These sorts of commands can be achieved by the reception and analysis of text messages.

Doing so is similar to the method we used in example 27.4. Once again, we will analyse the characters being sent from the GSM module via its serial out. However, there are two AT commands we need to send to the GSM module before we can receive SMSs, and one afterwards. The first one you already know:

AT+CMGF=1

Which sets the SMS mode to text. The second command is:

AT+CNMI=3,3,0,0

This command tells the GSM module to immediately send any new SMS data to the serial out. An example of this is shown in the terminal capture below:

Two text messages have been received since the module was turned on. You can see how the data is laid out. The blacked out number is the sender of the SMS. The number +61418706700 is the number for my carrier’s SMSC (short message service centre). Then we have the date and time. The next line is the contents of the text message – what we need to examine in our sketch.

The second text message in the example above is how we will structure our control SMS. Our sketch will wait for a # to come from the serial line, then consider the values after a, b, c and d – 0 for off, 1 for on. Finally, we need to send one more command to the GSM module after we have interpreted our SMS:

AT+CMGD=1,4

This deletes all the text messages from the SIM card. As there is a finite amount of storage space on the SIM, it is prudent to delete the incoming message after we have followed the instructions within. But now for our example. We will control four digital outputs, D9~12. For the sake of the exercise we are controlling an LED on each digital output, however you could do anything you like.

Although the sketch may seem long and complex, it is not – just follow it through and you will see what is happening:

// Example 27.5

char inchar; // Will hold the incoming character from the Serial Port.

int led1 = 9;

int led2 = 10;

int led3 = 11;

int led4 = 12;

void setup()

{

// prepare the digital output pins

pinMode(led1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led4, OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(led1, LOW);

digitalWrite(led2, LOW);

digitalWrite(led3, LOW);

digitalWrite(led4, LOW);

//Initialize GSM module serial port for communication.

Serial1.begin(9600);

delay(30000); // give time for GSM module to register on network etc.

Serial1.println("AT+CMGF=1"); // set SMS mode to text

delay(200);

Serial1.println("AT+CNMI=3,3,0,0"); // set module to send SMS data to serial out upon receipt

delay(200);

}

void loop()

{

//If a character comes in from the cellular module...

if(Serial1.available() >0)

{

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='#')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='a')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='0')

{

digitalWrite(led1, LOW);

}

else if (inchar=='1')

{

digitalWrite(led1, HIGH);

}

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='b')

{

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='0')

{

digitalWrite(led2, LOW);

}

else if (inchar=='1')

{

digitalWrite(led2, HIGH);

}

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='c')

{

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='0')

{

digitalWrite(led3, LOW);

}

else if (inchar=='1')

{

digitalWrite(led3, HIGH);

}

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='d')

{

delay(10);

inchar=Serial1.read();

if (inchar=='0')

{

digitalWrite(led4, LOW);

}

else if (inchar=='1')

{

digitalWrite(led4, HIGH);

}

delay(10);

}

}

Serial1.println("AT+CMGD=1,4"); // delete all SMS

}

}

}

}

}

And a demonstration video

showing this in action.

Conclusion

So there you have it – controlling your Arduino Mega’s digital outputs via a normal telephone or SMS. Now it is up to you and your imagination to find something to control, sensor data to return, or get up to other shenanigans. This shield and antenna is available from Tronixlabs. If you enjoyed this article, you may find this of interest – controlling AC power outlets via SMS. And if you enjoyed this article, or want to introduce someone else to the interesting world of Arduino – check out my book (now in a third printing!) “Arduino Workshop”.

Have fun and keep checking into

tronixstuff.com. Why not follow things on

twitter,

Google+, subscribe for email updates or RSS using the links on the right-hand column, or join our

forum – dedicated to the projects and related items on this website.

Sign up – it’s free, helpful to each other – and we can all learn something.

The post Tutorial – Arduino Mega and SM5100B GSM Cellular appeared first on tronixstuff.