Electricity Monitoring with a Light-to-Voltage Sensor, MQTT and some Duct Tape

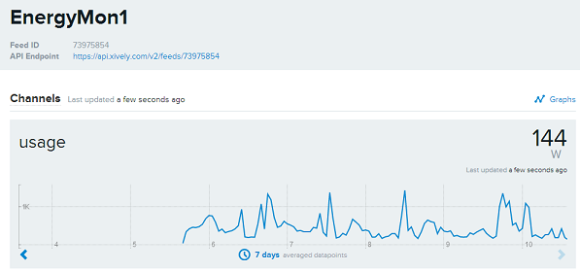

When it comes down to energy management, having real-time data is key. But rarely is up-to-the-minute kilowatt hour information given out freely by a Utility company, which makes it extremely hard to adjust spending habits during the billing cycle. So when we heard about [Jon]‘s project to translate light signals radiating out of his meter, we had to check it out.

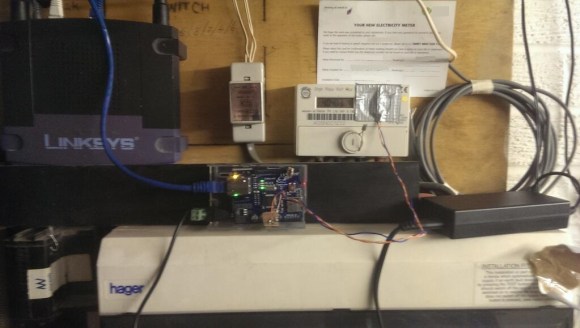

From the looks of it, his hardware configuration is relatively simple. All it uses is a TSL261 Light-to-Voltage sensor connected to an Arduino with an Ethernet shield attached. The sensor is then taped above the meter’s flashing LED, which flickers whenever a pulse is sent out indicating every time a watt of electricity is used. His configuration is specific to the type of meter that was installed by his Utility, and there is no guarantee that all the meters deployed by that company are the same. But it is a good start towards a better energy monitoring solution.

And the entire process is documented on [Jon]’s website, allowing for more energy-curious people to see what it took to get it all hooked up. In it, he describes how to get started with MQTT, which is a machine-to-machine (M2M)/”Internet of Things” connectivity protocol, to produce a real-time graph, streaming data in from a live feed.

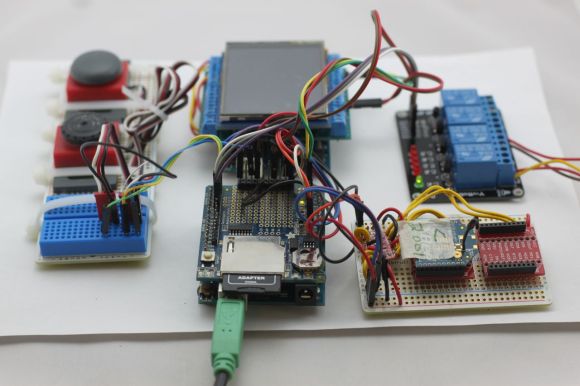

Now, with all this valuable information, other applications can be built on top of it. Interfacing with something like the Pinoccio microcontroller system can allow for devices to be turned off during peak-power times, helping to reduce the billing price at the end of the month.

Energy-intelligence platforms like this assist in conserving electricity while keeping the rate-payer consistently informed of their power usage habits. A real win, win. However, we still need to figure out how to (legally) extract the data from other types of meters.

One example is to harvest the information wirelessly with a special USB dongle to gather the data emitting from the Utility meter. But this only works for that brand of meter. Another solution is to read infrared flashes with an AVR, a resistor, a capacitor, and a phototransistor, which is similar to what [Jon] created above.

So, what kind of meter do you have? And, do you think there is a better way to extract the kWh data? Let us know in the comments, and let’s see what we can come up with.

Filed under: home hacks

The project featured in this post is an entry in

The project featured in this post is an entry in  In the near future, we will all reside in households that contain hundreds of little devices intertwingled together with an easily connectable and controllable network of sensors. For years, projects have been appearing all around the world,

In the near future, we will all reside in households that contain hundreds of little devices intertwingled together with an easily connectable and controllable network of sensors. For years, projects have been appearing all around the world,  Some people really love their smoothies. We mean really, really, love smoothies and everything about making them, especially the blenders. [Adam] is a big fan of blenders, and wanted to verify that his Vitamix blenders ran as fast as the manufacturer claimed. So he built not one, but

Some people really love their smoothies. We mean really, really, love smoothies and everything about making them, especially the blenders. [Adam] is a big fan of blenders, and wanted to verify that his Vitamix blenders ran as fast as the manufacturer claimed. So he built not one, but