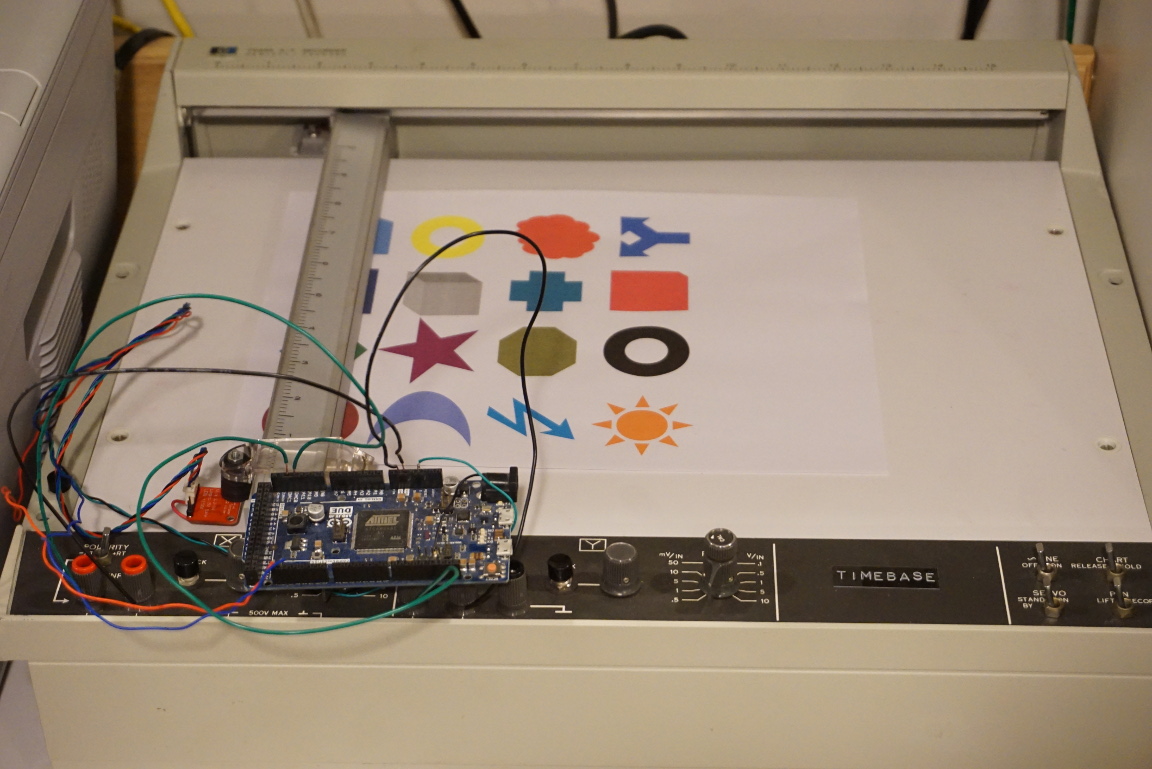

When you think of image processing, you probably don’t think of the Arduino. [Jan Gromes] did, though. Using a camera and an Arduino Mega, [Jan] was able to decode input from an Arduino-connected camera into raw image data. We aren’t sure about [Jan’s] use case, but we can think of lots of reasons you might want to know what is hiding inside a compressed JPEG from the camera.

The Mega is key, because–as you might expect–you need plenty of memory to deal with photos. There is also an SD card for auxiliary storage. The camera code is straightforward and saves the image to the SD card. The interesting part is the decoding.

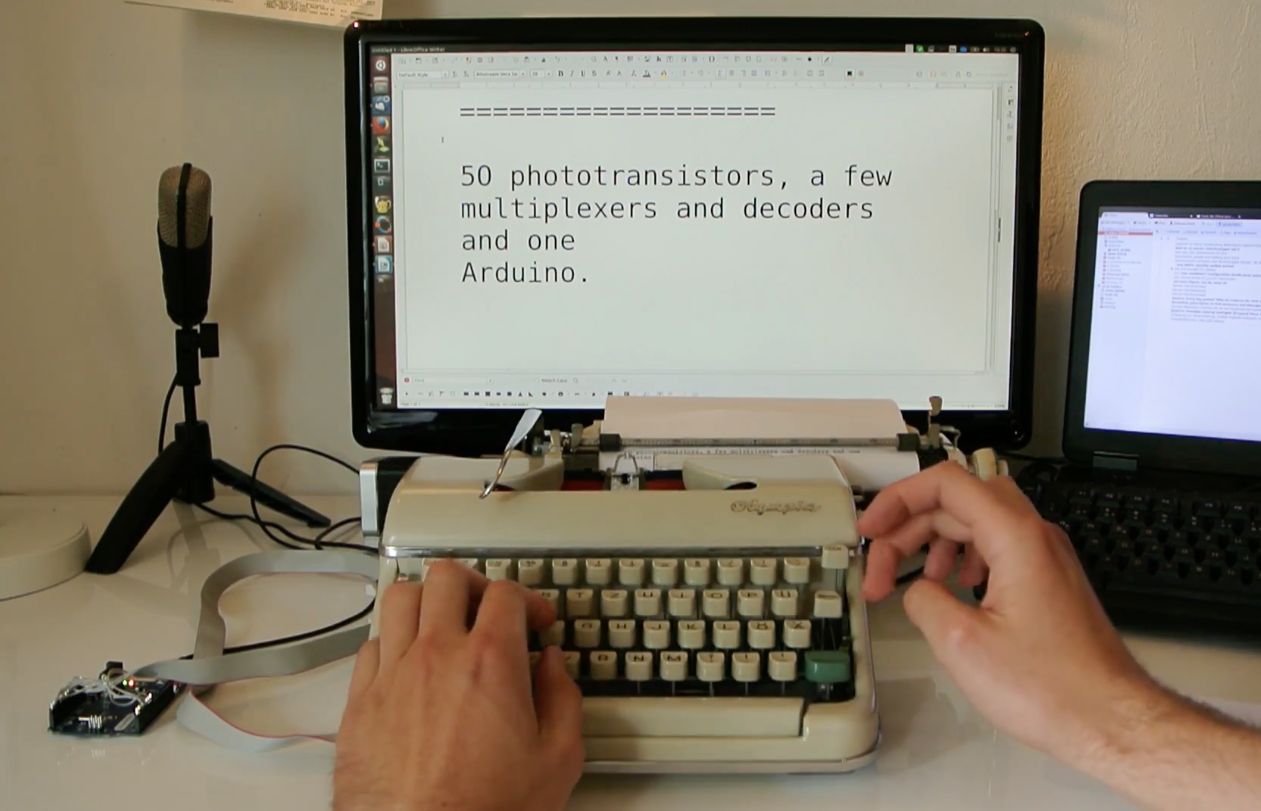

The use case mentioned in the post is sending image data across a potentially lossy communication channel. Because JPEG is compressed in a lossy way, losing some part of a JPEG will likely render it useless. But sending raw image data means that lost or wrong data will just cause visual artifacts (think snow on an old TV screen) and your brain is pretty good at interpreting lossy images like that.

Just to test that theory, we took one of [Joe Kim’s] illustrations, saved it as a JPEG and corrupted just a few bytes in a single spot in it. You can see the before (left) and after (right) picture below. You can make it out, but the effect of just a few bytes in one spot is far-reaching, as you can see.

The code uses a library that returns 16-bit RGB images. The library was meant for displaying images on a screen, but then again it doesn’t really know what you are doing with the results. It isn’t hard to imagine using the data to detect a specific color, find edges in the image, detect motion, and other simple tasks.

Sending the uncompressed image data might be good for error resilience, but it isn’t good for impatient people. At 115,200 baud, [Jan] says it takes about a minute to move a raw picture from the Arduino to a PC.

We’ve seen the Arduino handle a single pixel at a time. Even in color. The Arduino might not be your first choice for an image processing platform, but clearly, you can do some things with it.

Filed under:

Arduino Hacks