PID Control with Arduino

Experience — or at least education — often makes a big difference to having a successful project. For example, if you didn’t think about it much, you might think it is simple to control the temperature of something that is heating. Just turn on the heater if it is cold and turn it off when you hit the right temperature, right? That is one approach — sometimes known as bang-bang — but you’ll find there a lot of issues with that approach. Best practice is to use a PID or Proportional/Integral/Derivative control. [Electronoob] has a good tutorial about how to pull this off with an Arduino. You can also see a video, below.

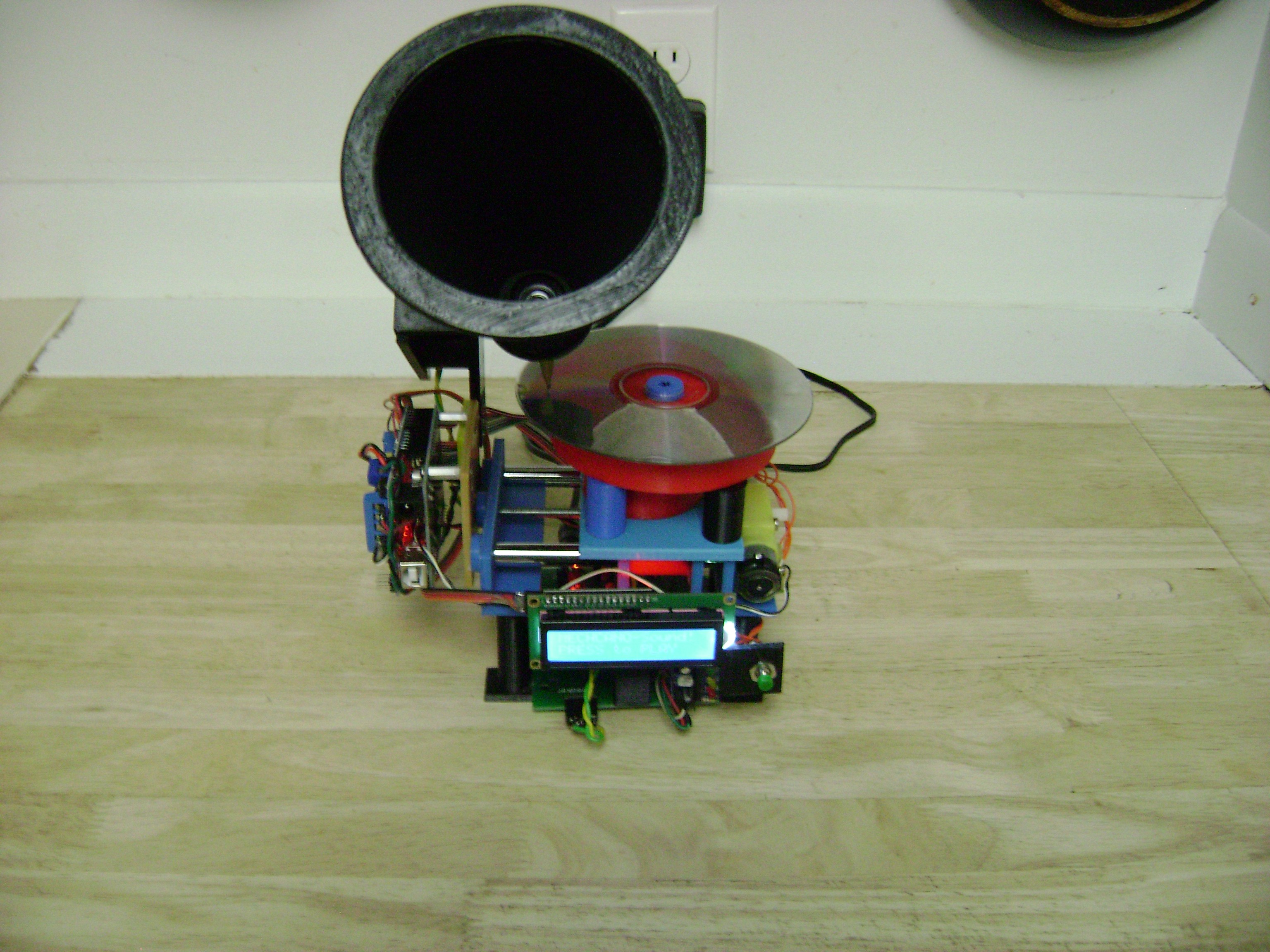

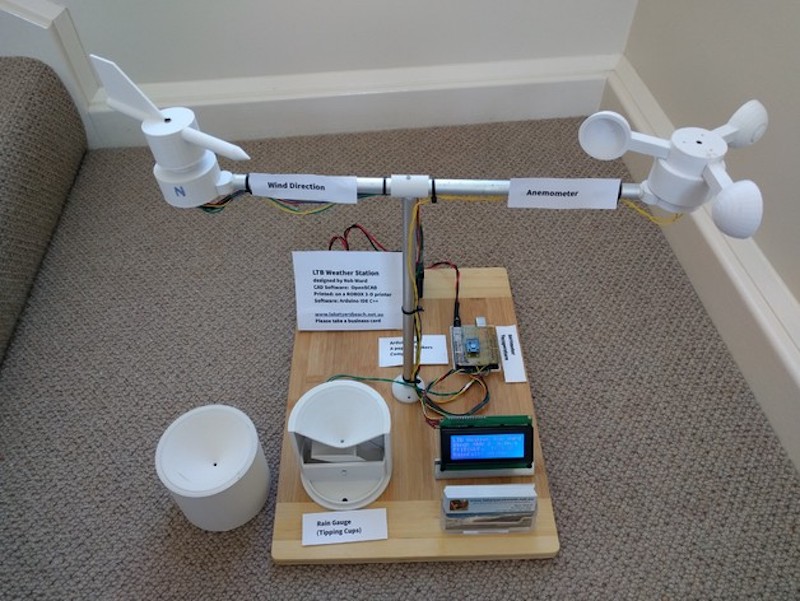

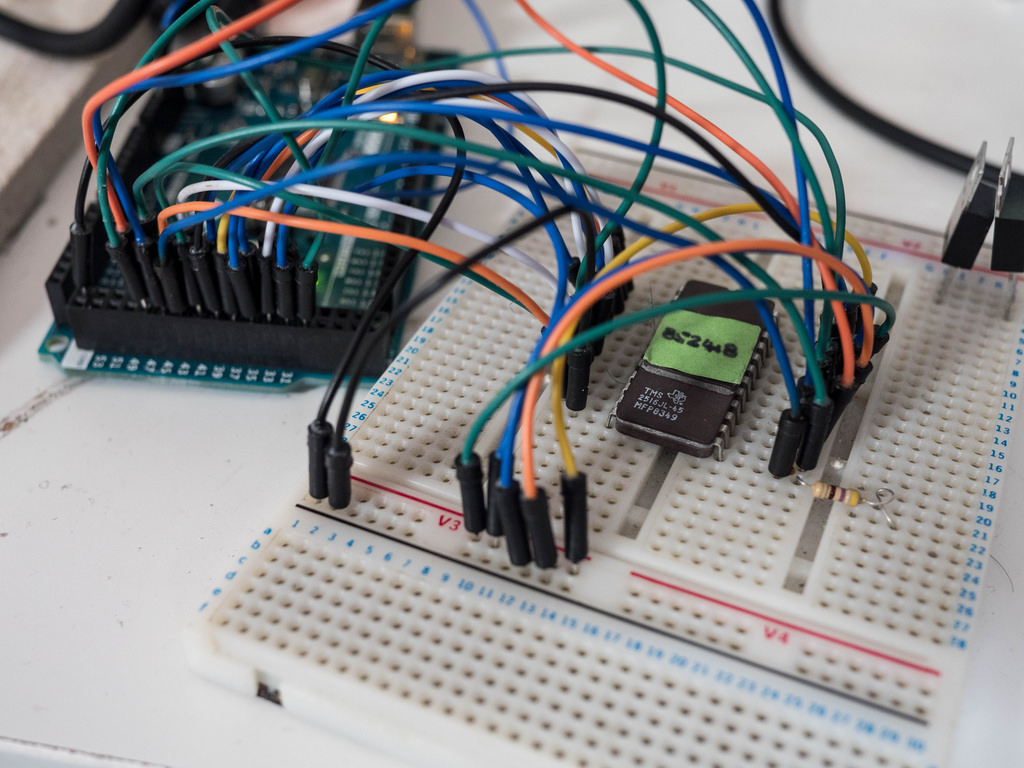

The demo uses a 3D printer hot end, a thermocouple, a MAX6675 that reads the thermocouple, and an Arduino. There’s also an LCD display and a FET to control the heater.

The idea behind a PID controller is that you measure the difference between the current temperature and the desired temperature known as the setpoint. The proportional gain tells you how much output occurs due to that difference. So if the setpoint is way off, the proportional term will generate a lot of output to the heater. If it is close, only a little bit of output will result. This helps prevent overshoot where the temperature goes too high and has to come back down.

The integral term adds a little bit to the output based on the cumulative error over time. The derivative term reacts to changes in the temperature difference. For example, if something external causes the temperature to drop suddenly, the derivative term can goose the output to compensate.

However, the operative word is “can.” Part of setting up a PID is finding the coefficients for each term which for some systems could be zero or even negative (indicating a reverse effect). There are a lot of other subtleties, too, like what happens if the output stops affecting the temperature for a long period and the integral amount grows to unmanageable magnitude.

By the way, we’ve covered a PID library for Arduino before. While this post talks about temperature, PID control is used for everything from flight control to levitation.