Feed Your Fasteners in Line, With a Bowl Feeder

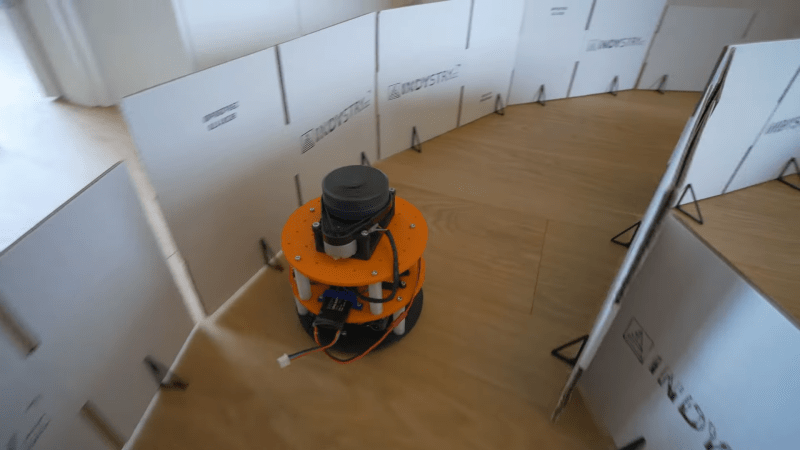

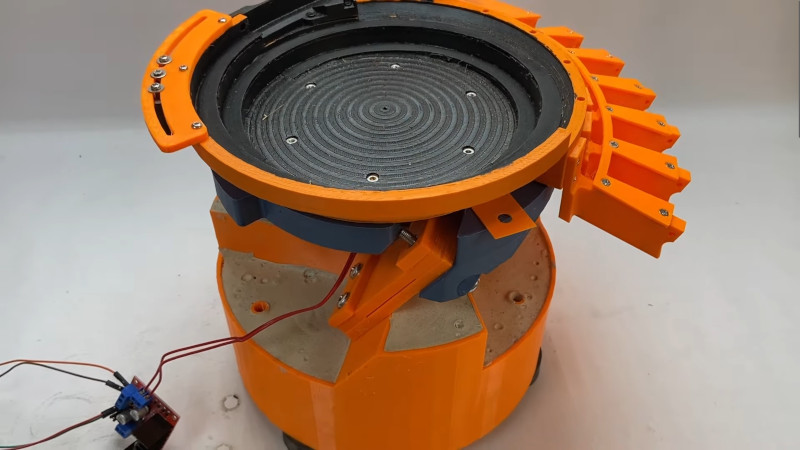

If you spend much time around industrial processes, you may have seen a vibrating bowl feeder at work. It’s a clever but simple machine that takes an unruly pile of screws or nuts and bolts, and delivers them in a line the correct way up. They do this by shaking the pile of fasteners in a specific way — a spiral motion which encourages them to work to the edge of the pile and align themselves on a spiral track which leads to a dispenser. It’s a machine [Fraens] has made from 3D printed parts, and as he explains in the video below the break, there’s more to this than meets the eye.

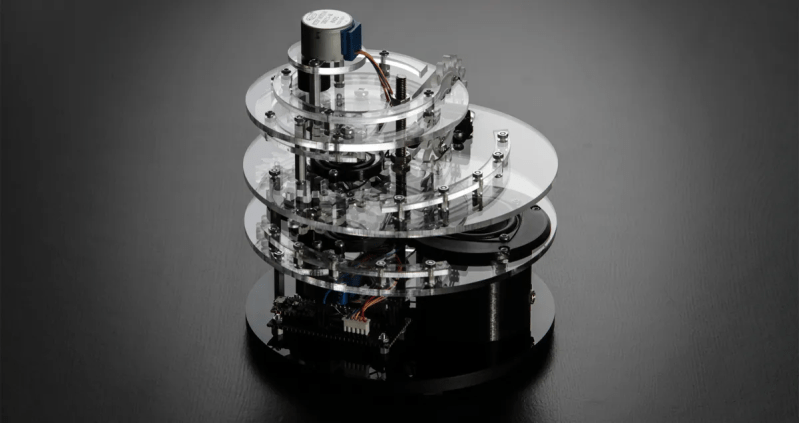

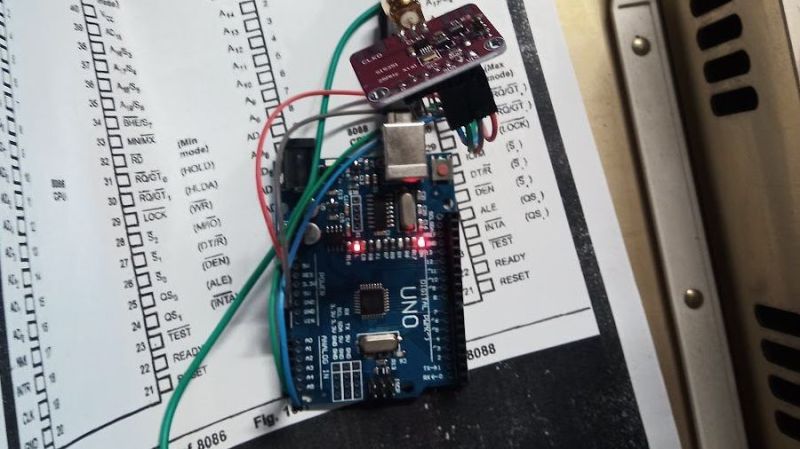

The basic form of the machine has a weighted base and an upper bowl on three angled springs. Between the two is an electromagnet, which provides the force for the vibration. The electromagnet needed to be driven with a sine wave which he makes with an Arduino and delivers as PWM via an H-bridge, but the meat of this project comes in balancing the force and frequency with the stiffness of the springs. He shows us the enormous pile of test prints made before the final result was achieved, and it’s a testament to the amount of work put into this project. The final sequence of a variety of objects making the march round the spiral is pure theatre, but we can see his evident satisfaction in a job well done.

Oddly this isn’t the first bowl feeder we’ve seen, though it may be one of the most accomplished. We particularly like this tiny example for SMD parts.