Spot This DIY Electronic Load’s Gracefully Hidden Hacks

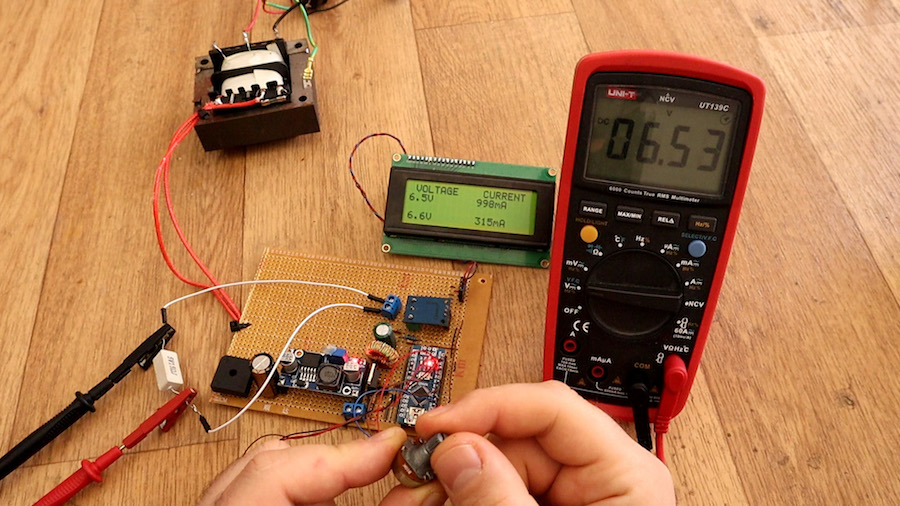

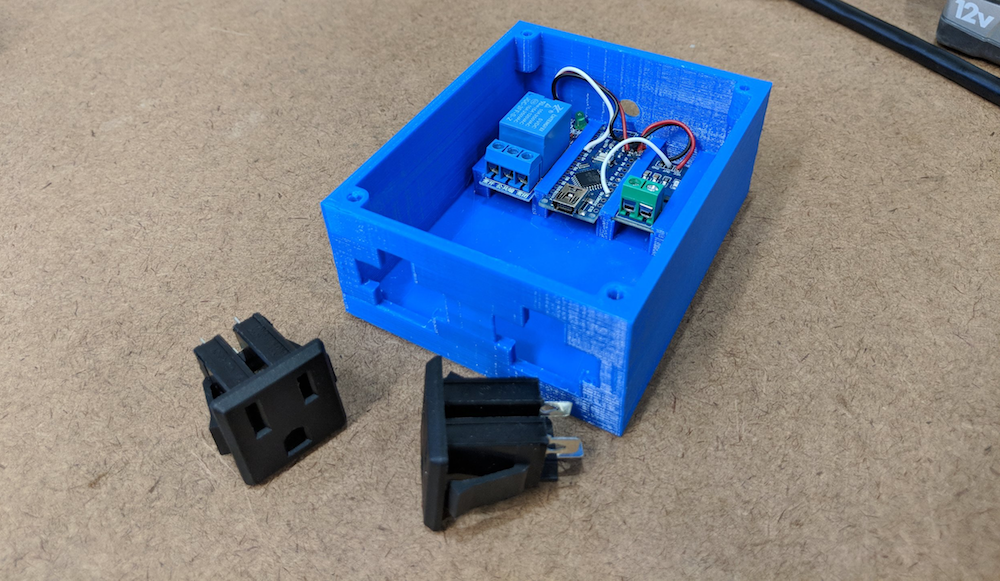

Sometimes it’s necessary to make do with whatever parts one has on hand, but the results of squashing a square peg into a round hole are not always as elegant as [Juan Gg]’s programmable DC load with rotary encoder. [Juan] took a design for a programmable DC load and made it his own in quite a few different ways, including a slick 3D-printed enclosure and color faceplate.

The first thing to catch one’s eye might be that leftmost seven-segment digit. There is a simple reason it doesn’t match its neighbors: [Juan] had to use what he had available, and that meant a mismatched digit. Fortunately, 3D printing one’s own enclosure meant it could be gracefully worked into the design, instead of getting a Dremel or utility knife involved. The next is a bit less obvious: the display lacked a decimal point in the second digit position, so an LED tucked in underneath does the job. Finally, the knob on the right could reasonably be thought to be a rotary encoder, but it’s actually connected to a small DC motor. By biasing the motor with a small DC voltage applied to one lead and reading the resulting voltage from the other, the knob’s speed and direction can be detected, doing a serviceable job as rotary encoder substitute.

The first thing to catch one’s eye might be that leftmost seven-segment digit. There is a simple reason it doesn’t match its neighbors: [Juan] had to use what he had available, and that meant a mismatched digit. Fortunately, 3D printing one’s own enclosure meant it could be gracefully worked into the design, instead of getting a Dremel or utility knife involved. The next is a bit less obvious: the display lacked a decimal point in the second digit position, so an LED tucked in underneath does the job. Finally, the knob on the right could reasonably be thought to be a rotary encoder, but it’s actually connected to a small DC motor. By biasing the motor with a small DC voltage applied to one lead and reading the resulting voltage from the other, the knob’s speed and direction can be detected, doing a serviceable job as rotary encoder substitute.

The project’s GitHub repository contains the Arduino code for [Juan]’s project, which has its roots in a design EEVblog detailed for an electronic load. For those of you who prefer your DIY rotary encoders to send discrete clicks and pulses instead of an analog voltage, a 3D printed wheel and two microswitches will do the job.