Gosh, what a shame: it turns out that perhaps 2 billion phones won’t be capable of COVID-19 contact-tracing using the API that Google and Apple are jointly developing. The problem is that the scheme the two tech giants have concocted, which Elliot Williams expertly dissected recently, is based on Bluetooth LE. If a phone lacks a BLE chipset, then it won’t work with apps built on the contact-tracing API, which uses the limited range of BLE signals as a proxy for the physical proximity of any two people. If a user is reported to be COVID-19 positive, all the people whose BLE beacons were received by the infected user’s phone within a defined time period can be anonymously notified of their contact. As Elliot points out, numerous questions loom around this scheme, not least of which is privacy, but for now, something like a third of phones in mature smartphone markets won’t be able to participate, and perhaps two-thirds of the phones in developing markets are not compatible. For those who don’t like the privacy-threatening aspects of this scheme, pulling an old phone out and dusting it off might not be a bad idea.

We occasionally cover stories where engineers in industrial settings use an Arduino for a quick-and-dirty automation solution. This is uniformly met with much teeth-gnashing and hair-rending in the comments asserting that Arduinos are not appropriate for industrial use. Whether true or not, such comments miss the point that the Arduino solution is usually a stop-gap or proof-of-concept deal. But now the purists and pedants can relax, because Automation Direct is offering Arduino-compatible, industrial-grade programmable controllers. Their ProductivityOpen line is compatible with the Arduino IDE while having industrial certifications and hardening against harsh conditions, with a rich line of shields available to piece together complete automation controllers. For the home-gamer, an Arduino in an enclosure that can withstand harsh conditions and only cost $49 might fill a niche.

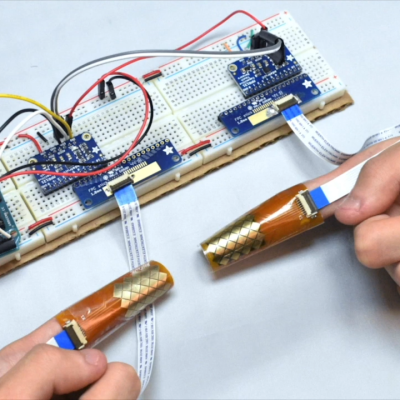

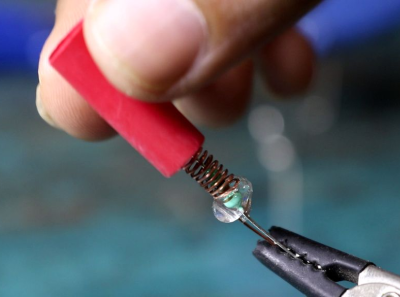

Speaking of Arduinos and Arduino accessories, better watch out if you’ve got any modules and you come under the scrutiny of an authoritarian regime, because you could be accused of being a bomb maker. Police in Hong Kong allegedly arrested a 20-year-old student and posted a picture of parts he used to manufacture a “remote detonated bomb”. The BOM for the bomb was strangely devoid of anything with wireless capabilities or, you know, actual explosives, and instead looks pretty much like the stuff found on any of our workbenches or junk bins. Pretty scary stuff.

If you’ve run through every binge-worthy series on Netflix and are looking for a bit of space-nerd entertainment, have we got one for you. Scott Manley has a new video that goes into detail on the four different computers used for each Apollo mission. We knew about the Apollo Guidance Computers that guided the Command Module and the Lunar Module, and the Launch Vehicle Digital Computer that got the whole stack into orbit and on the way to the Moon, but we’d never heard of the Abort Guidance System, a backup to the Lunar Module AGC intended to get the astronauts back into lunar orbit in the event of an emergency. And we’d also never heard that there wasn’t a common architecture for these machines, to the point where each had its own word length. The bit about infighting between MIT and IBM was entertaining too.

And finally, if you still find yourself with time on your hands, why not try your hand at pen-testing a military satellite in orbit? That’s the offer on the table to hackers from the US Air Force, proprietor of some of the tippy-toppest secret hardware in orbit. The Hack-A-Sat Space Security Challenge is aimed at exposing weaknesses that have been inadvertantly baked into space hardware during decades of closed development and secrecy, vulnerabilities that may pose risks to billions of dollars worth of irreplaceable assets. The qualification round requires teams to hack a grounded test satellite before moving on to attacking an orbiting platform during DEFCON in August, with prizes going to the winning teams. Get paid to hack government assets and not get arrested? Maybe 2020 isn’t so bad after all.