PlatformIO and Visual Studio Take over the World

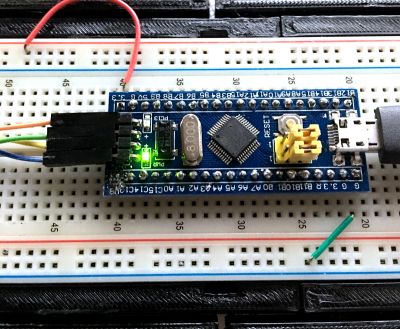

In a recent post, I talked about using the “Blue Pill” STM32 module with the Arduino IDE. I’m not a big fan of the Arduino IDE, but I will admit it is simple to use which makes it good for simple things.

I’m not a big fan of integrated development environments (IDE), in general. I’ve used plenty of them, especially when they are tightly tied to the tool I’m trying to use at the time. But when I’m not doing anything special, I tend to just write my code in emacs. Thinking about it, I suppose I really don’t mind an IDE if it has tools that actually help me. But if it is just a text editor and launches a few commands, I can do that from emacs or another editor of my choice. The chances that your favorite IDE is going to have as much editing capability and customization as emacs are close to zero. Even if you don’t like emacs, why learn another editor if there isn’t a clear benefit in doing so?

There are ways, of course, to use other tools with the Arduino and other frameworks and I decided to start looking at them. After all, how hard can it be to build Arduino code? If you want to jump straight to the punch line, you can check out the video, below.

Turns Out…

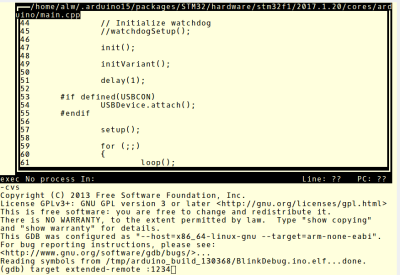

It turns out, the Arduino IDE does a lot more than providing a bare-bones editor and launching a few command line tools. It also manages a very convoluted build process. The build process joins a lot of your files together, adds headers based on what it thinks you are doing, and generally compiles one big file, unless you’ve expressly included .cpp or .c files in your build.

That means just copying your normal Arduino code (I hate to say sketch) doesn’t give you anything you can build with a normal compiler. While there are plenty of makefile-based solutions, there’s also a tool called PlatformIO that purports to be a general-purpose solution for building on lots of embedded platforms, including Arduino.

About PlatformIO

Although PlatformIO claims to be an IDE, it really is a plugin for the open source Atom editor. However, it also has plugins for a lot of other IDEs. Interestingly enough, it even supports emacs. I know not everyone appreciates emacs, so I decided to investigate some of the other options. I’m not talking about VIM, either.

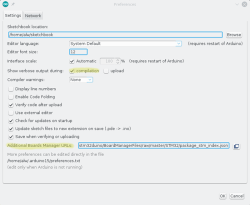

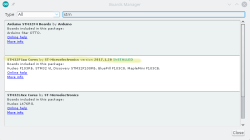

I wound up experimenting with two IDEs: Atom and Microsoft Visual Studio Code. Since PlatformIO has their 2.0 version in preview, I decided to try it. You might be surprised that I’m using Microsoft’s Code tool. Surprisingly, it runs on Linux and supports many things through plugins, including an Arduino module and, of course, PlatformIO. It is even available as source under an MIT license. The two editors actually look a lot alike, as you can see.

PlatformIO supports a staggering number of boards ranging from Arduino to ESP82666 to mBed boards to Raspberry Pi. It also supports different frameworks and IDEs. If you are like me and just like to be at the command line, you can use PlatformIO Core which is command line-driven.

In fact, that’s one of the things you first notice about PlatformIO is that it can’t decide if it is a GUI tool or a command line tool. I suspect some of that is in the IDE choice, too. For example, with Code, you have to run the projection initialization tool in a shell prompt. Granted, you can open a shell inside Code, but it is still a command line. Even on the PlatformIO IDE (actually, Atom), changing the Blue Pill framework from Arduino to mBed requires opening an INI file and changing it. Setting the upload path for an FRDM-KL46 required the same sort of change.

Is it Easy?

Don’t get me wrong. I personally don’t mind editing a file or issuing a command from a prompt. However, it seems like this kind of tool will mostly appeal to someone who does. I like that the command line tools exist. But it does make it seem odd when some changes are done in a GUI and some are done from the command line.

That’s fixable, of course. However, I do have another complaint that I feel bad for voicing because I don’t have a better solution. PlatformIO does too much. In theory, that’s the strength of it. I can write my code and not care how the mBed libraries or written or the Arduino tools munge my source code. I don’t even have to set up a tool chain because PlatformIO downloads everything I need the first time I use it.

When that works it is really great. The problem is when it doesn’t. For example, on the older version of PlatformIO, I had trouble getting the mBed libraries to build for a different target. I dug around and found the issue but it wasn’t easy. Had I built the toolchain and been in control of the process, I would have known better how to troubleshoot.

In the end, too, you will have to troubleshoot. PlatformIO aims at moving targets. Every time the Arduino IDE or the mBed frameworks or anything else changes, there is a good chance it will break something. When it does, you are going to have to work to fix it until the developers fix it for you. If you can do that, it is a cost in time. But I suspect the people who will be most interested in PlatformIO will be least able to fix it when it breaks.

Bottom Line

If you want to experiment with a different way of building programs — and more importantly, a single way to create and build — you should give PlatformIO a spin. When it works, it works well. Here are a few links to get you started:

- The PlatformIO IDE (requires Atom)

- PlatformIO Core (not needed if you install an IDE package)

- Visual Studio Code (install PlatformIO from within the IDE)

Bottom line, when it works, it works great. When it doesn’t it is painful. Should you use it? It is handy, there’s no doubt about that. The integration with Code is pretty minimal. The Atom integration — while not perfect — is much more seamless. However, if you learn to use the command line tools, it almost doesn’t matter. Use whatever editor you like, and I do like that. If you do use it, just hope it doesn’t break and maybe have a backup plan if it does.

Filed under: Arduino Hacks, ARM, Hackaday Columns, reviews, Skills

Hackaday readers of a recent vintage might remember an old US Robotics modem that plugged into your computer and phone line, allowing you to access MySpace or Geocities. Yes, if someone picked up the phone, your connection would drop. Those of us with just a little more experience under our belts will remember the acoustic coupler modem — a cradle that held a phone handset that connected your computer (indirectly) to the phone line.

Hackaday readers of a recent vintage might remember an old US Robotics modem that plugged into your computer and phone line, allowing you to access MySpace or Geocities. Yes, if someone picked up the phone, your connection would drop. Those of us with just a little more experience under our belts will remember the acoustic coupler modem — a cradle that held a phone handset that connected your computer (indirectly) to the phone line.