MIL-SPEC Keyboard Now Salutes USB

When [easyjo] picked up this late ’80s Marconi mil-spec keyboard for cheap, he knew it wouldn’t be easy to convert it to USB — just that it would be worth it. Spoiler alert: those LEDs aren’t a mod, they’re native. They get their interesting shape from the key traces, which are in the four corners.

Despite having way-cool buttons such as WPNS HOLD, and the fact that Control is on the home row where it belongs, this keyboard does not look fun to type on at all for any length of time. Of course, the point of this keyboard is not comfort, but a reliable input device that keeps out dust, sweat, liquids, and the enemy.

Despite having way-cool buttons such as WPNS HOLD, and the fact that Control is on the home row where it belongs, this keyboard does not look fun to type on at all for any length of time. Of course, the point of this keyboard is not comfort, but a reliable input device that keeps out dust, sweat, liquids, and the enemy.

This is probably why the controller is embedded into the underside of the key switch PCB instead of living on its own board. [easyjo] tried to analyze the signals from the existing 26-pin connector, but it didn’t work out.

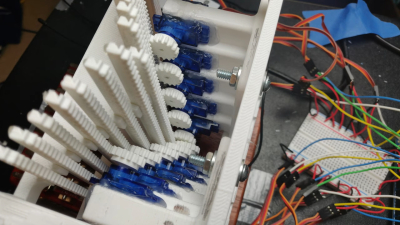

So once he was able to decode the matrix, he removed the controller chip and wired the rows and columns directly to an Arduino Leonardo. Fortunately, the LEDs were just a matter of powering their columns from the front side of the board.

The availability of certain kinds of military surplus can make for really interesting modernization projects, like adding POTS to a field telephone.

Via r/duino