Store and replay this robot’s movements from your phone

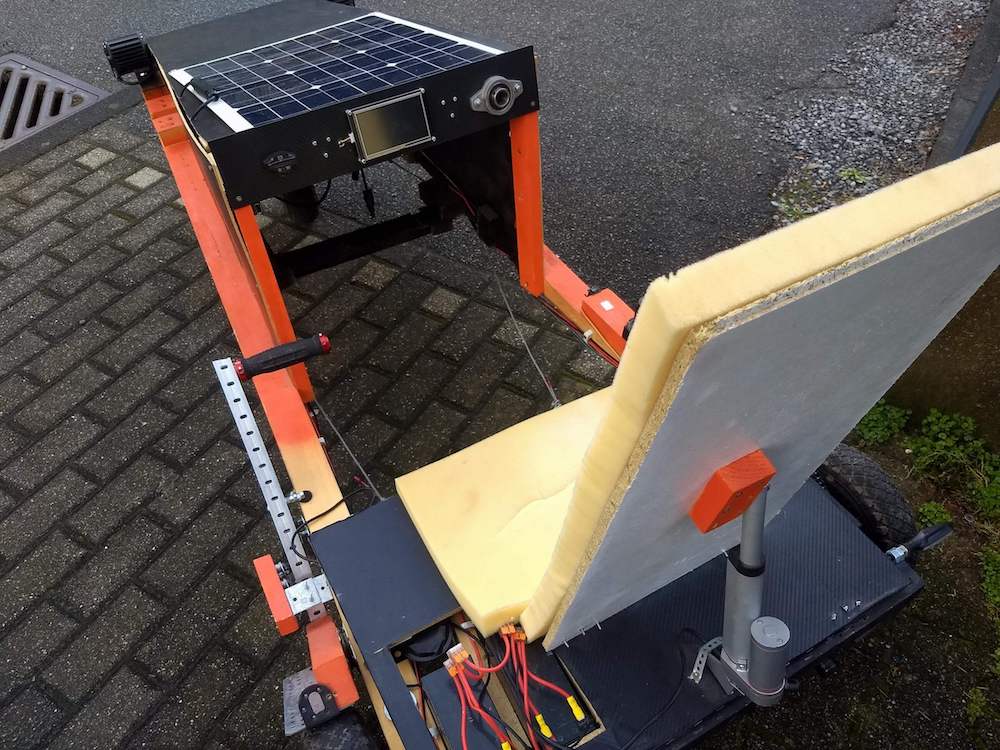

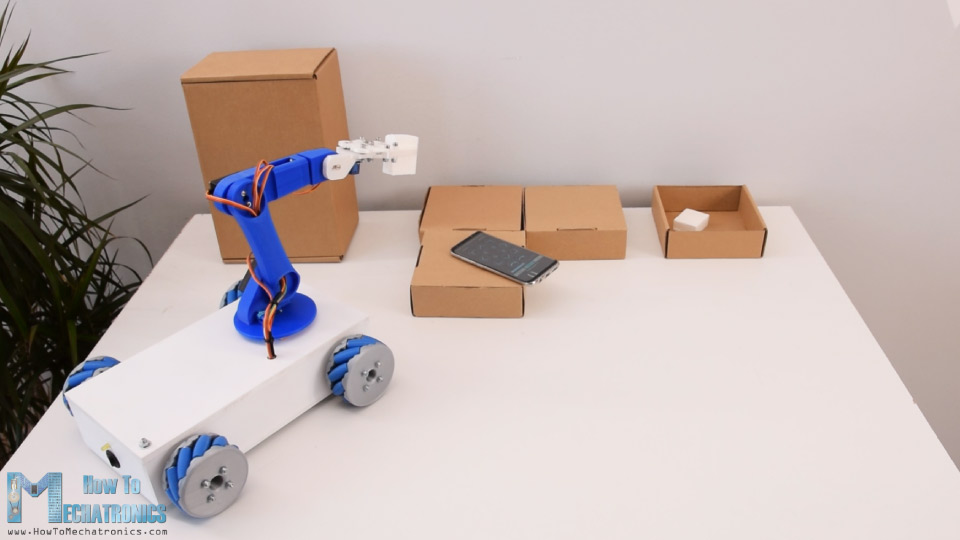

Robotic arms can be interesting, as are robots that roll around—especially on a semi-exotic Mecanum wheel setup. Dejan Nedelkovski’s latest How To Mechatronics build, however, combines both into one package.

This project actually starts out in a previous post, where he constructs the moving base with Mecanum wheels, enabling it to slide and rotate in any direction.

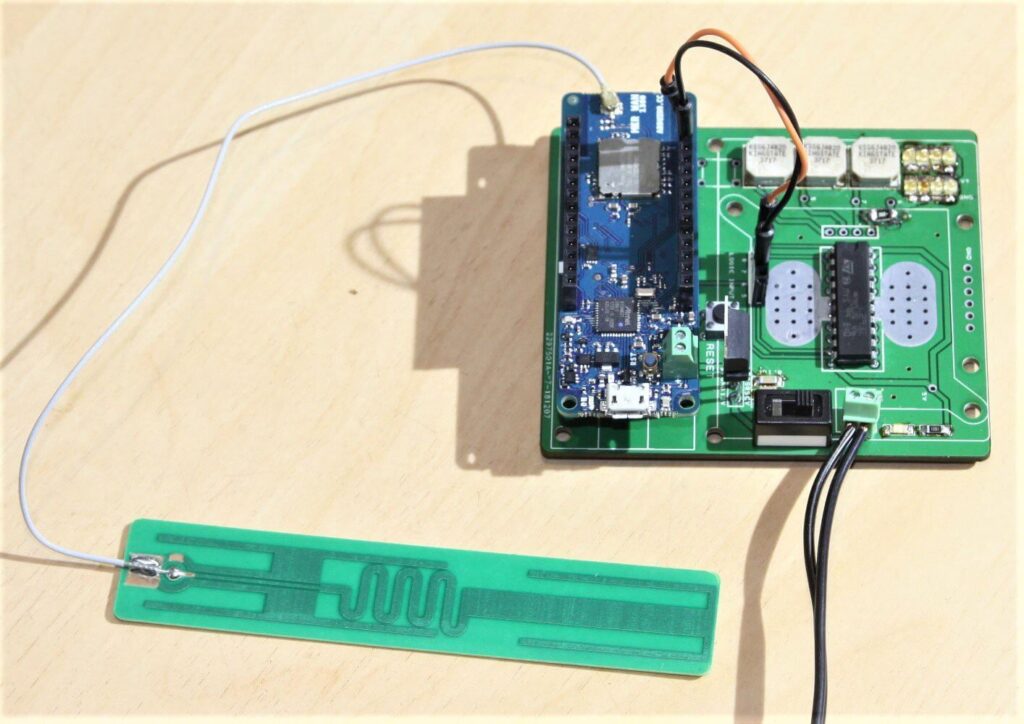

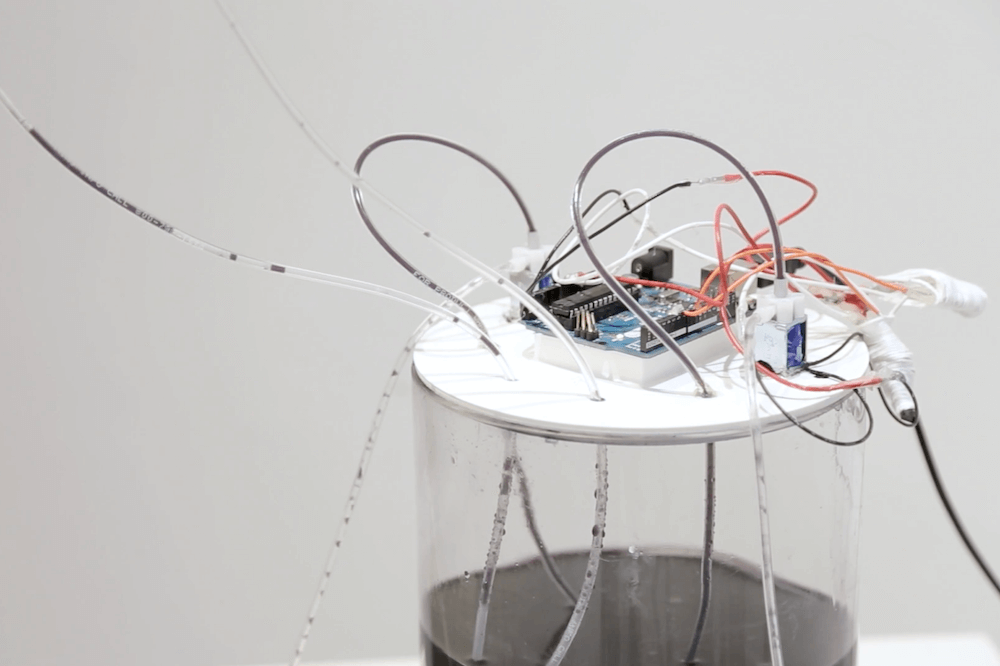

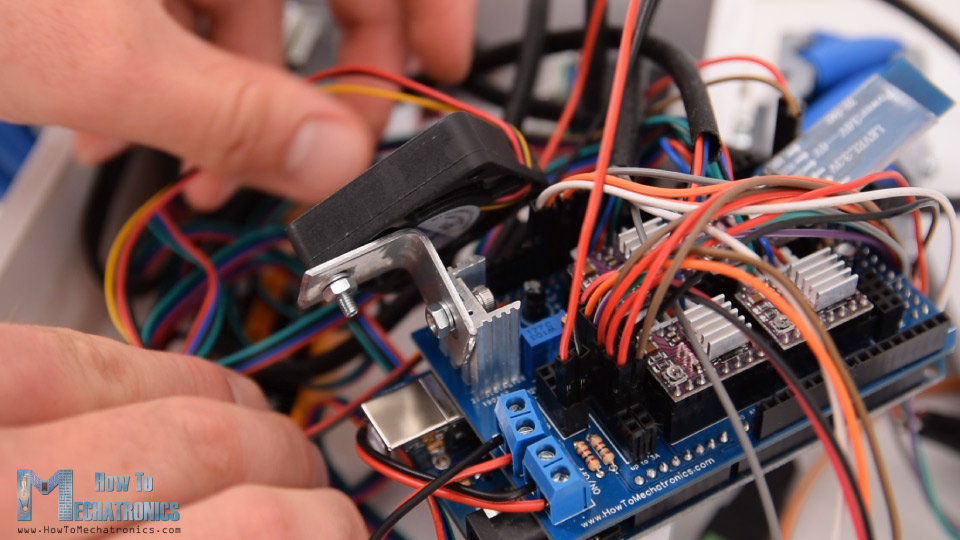

In this final(?) stage, he adds a five-axis robot arm mounted on top of its boxy frame, or six-axis if you count the gripper. Either way, the arm uses a total of six servos for actuation, and the base of the bot travels around under the power of four stepper motors. Each motor is controlled by an Arduino Mega, using a custom shield, allowing repeatable movements in any direction. These can be stored and replayed via the robot’s custom Android app as desired.