Wiring was Arduino before Arduino

Hernando Barragán is the grandfather of Arduino of whom you’ve never heard. And after years now of being basically silent on the issue of attribution, he’s decided to get some of his grudges off his chest and clear the air around Wiring and Arduino. It’s a long read, and at times a little bitter, but if you’ve been following the development of the Arduino vs Arduino debacle, it’s an important piece in the puzzle.

Wiring, in case you don’t know, is where digitalWrite() and company come from. Maybe even more importantly, Wiring basically incubated the idea of building a microcontroller-based hardware controller platform that was simple enough to program that it could be used by artists. Indeed, it was intended to be the physical counterpart to Processing, a visual programming language for art. We’ve always wondered about the relationship between Wiring and Arduino, and it’s good to hear the Wiring side of the story. (We actually interviewed Barragán earlier this year, and he asked that we hold off until he published his side of things on the web.)

The short version is that Arduino was basically a fork of the Wiring software, re-branded and running on a physical platform that borrowed a lot from the Wiring boards. Whether or not this is legal or even moral is not an issue — Wiring was developed fully open-source, both software and hardware, so it was Massimo Banzi’s to copy as much as anyone else’s. But given that Arduino started off as essentially a re-branded Wiring (with code ported to a trivially different microcontroller), you’d be forgiven for thinking that somewhat more acknowledgement than “derives from Wiring” was appropriate.

The story of Arduino, from Barragán’s perspective, is actually a classic tragedy: student comes up with a really big idea, and one of his professors takes credit for it and runs with it.

This story begins in 2003 as Barragán was a Masters student at the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea (IDII) in Italy. He was advised and heavily influenced by Casey Reas, one of the two authors of Processing.

At the same time, Massimo Banzi is teaching a class in essentially microcontrollers-for-designers at Ivrea using a PIC-based board called the Programma2003 and a curious language that you’ve never heard of, “JAL: Just Another Language“. At the time, there was no GCC support for the PIC, so the choices for open-source development were few. Worse, most of the design students are using Macs, and JAL only compiles on Windows. It wasn’t user friendly.

At the same time, Massimo Banzi is teaching a class in essentially microcontrollers-for-designers at Ivrea using a PIC-based board called the Programma2003 and a curious language that you’ve never heard of, “JAL: Just Another Language“. At the time, there was no GCC support for the PIC, so the choices for open-source development were few. Worse, most of the design students are using Macs, and JAL only compiles on Windows. It wasn’t user friendly.

Barragán’s thesis is a must-read if you want to know where Arduino comes from. The summary is everything you know now: it’d be revolutionary if one could make a hardware / software platform that were easy enough that artists and non-microcontroller-nerds could get into. This is exactly the revolution that was underway in the computer graphics front, powered by Processing. Make it open source and freely available, and you’ll take over the world. So he turned to the Atmel AVR chips, which had the GCC open-source toolchain behind it.

From Wiring to Arduino

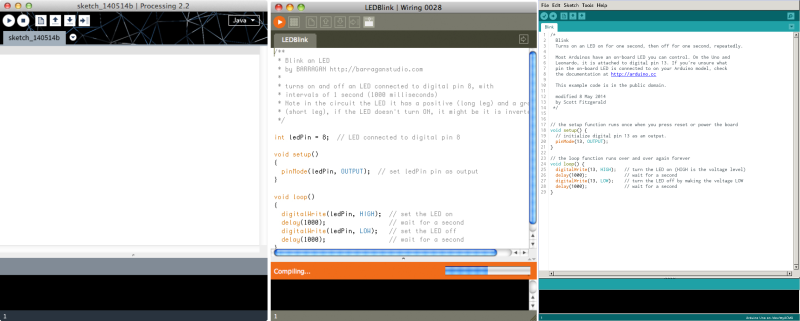

So by 2004, Barragán had a few prototypes of Wiring boards out, and he and his fellow students were using them informally for projects. The GUI will look ridiculously familiar if you’ve used Processing or Arduino. Since the students were already familiar with Processing, it made a lot of sense to just clone it — with Casey Reas’ blessing of course. Barragán wrote a little program that maybe you’ve heard of:

So by 2004, Barragán had a few prototypes of Wiring boards out, and he and his fellow students were using them informally for projects. The GUI will look ridiculously familiar if you’ve used Processing or Arduino. Since the students were already familiar with Processing, it made a lot of sense to just clone it — with Casey Reas’ blessing of course. Barragán wrote a little program that maybe you’ve heard of: Blink.

Now Barragán needed a faculty advisor at Ivrea, and his interests clearly aligned best with Massimo Banzi. So with his thesis work well underway and Reas’ backing, Barragán took on Banzi as his advisor. With Banzi and three other faculty members, the Wiring platform got its first real test-run, the “Strangely Familiar” workshop and show (PDF). It was a stunning success — in the space of only four weeks students actually made stuff.

Barragán graduated in 2004 and moved back to Colombia. The success of “Strangely Familiar” lead Massimo Banzi to drop Programma2003 like a hot potato and teach his physical design classes using Wiring.

Work began on the Arduino project, according to Banzi, because he wanted a board that was cheaper to make than the Wiring board. So he replaced the ATmega128 microcontroller for a cheaper, smaller version, and chopped off everything that wasn’t “essential” from the Wiring board, like the power LED. This became the “Wiring Lite” board — and eventually the first Arduino prototype.

Work began on the Arduino project, according to Banzi, because he wanted a board that was cheaper to make than the Wiring board. So he replaced the ATmega128 microcontroller for a cheaper, smaller version, and chopped off everything that wasn’t “essential” from the Wiring board, like the power LED. This became the “Wiring Lite” board — and eventually the first Arduino prototype.

Giving Arduino its Due

It is not the case that Arduino doesn’t acknowledge Wiring at all. They do. There are a few sentences in the first paragraph of the Credits section of the website, as mentioned above. That and $4.50 will buy you a Grande, Quad, Nonfat, One-Pump, No-Whip, Mocha, but how much more can one ask for?

The Arduino project has been marketed with extreme savvy, something that cannot be said of Wiring. Banzi hooked up with influential people in the US, eventually friend-of-a-friending himself into contact with Dale Dougherty, who invented not just “Web 2.0” but also the “Maker Movement” and Make Magazine. Arduino and Make was a match made in heaven, and the rest is history.

But as mentioned at the top of the article, this is a classic tale of woe. Banzi had better connections and more marketing drive and skill. He pushed the exact same project — rebranded — a lot harder, better, and further than Barragán did, or probably could. Arduino is a household name simply for that reason. If Massimo Banzi hadn’t been behind the wheel, it’s unlikely that you’d be complaining about how many Wiring-based projects we feature.

And, being open-source software and hardware, Barragán gave away the shop. He probably (naïvely) expected to get more credit from his former advisor, or even get invited along on the ride. He asks why Arduino forked Wiring instead of continuing to work with him, and the answer is absolutely clear — Arduino was taking it for their own. And they could. It’s not nice, but that’s business.

Still, we feel Barragán’s pain. So we’re glad, after a decade of silence, that Barragán is speaking out on behalf of himself and Wiring, because it sets the record straight and because his project really was “Arduino” before there was an Arduino.

Filed under: Arduino Hacks, Featured, news

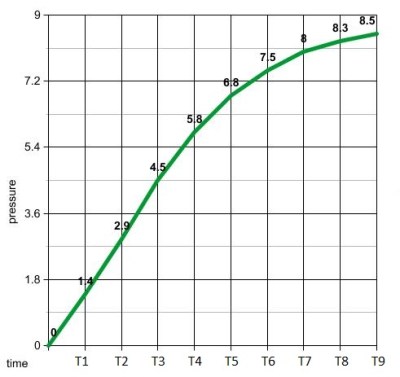

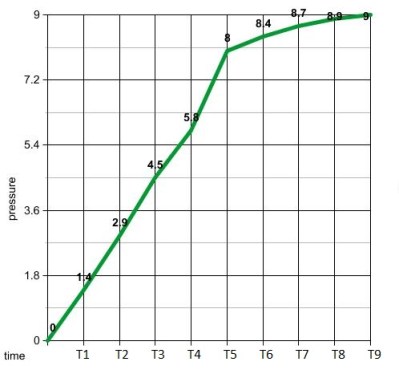

running a calculus function on an Arduino presents a seemingly impossible scenario. In this article, we’re going to explore the idea of using derivative like techniques with a microcontroller. Let us be reminded that the derivative provides an instantaneous rate of change. Getting an instantaneous rate of change when the function is known is easy. However, when you’re working with a microcontroller and varying analog data without a known function, it’s not so easy. Our goal will be to get an average rate of change of the data. And since a microcontroller is many orders of magnitude faster than the rate of change of the incoming data, we can calculate the average rate of change over very small time intervals. Our work will be based on the fact that the average rate of change and instantaneous rate of change are the same over short time intervals.

running a calculus function on an Arduino presents a seemingly impossible scenario. In this article, we’re going to explore the idea of using derivative like techniques with a microcontroller. Let us be reminded that the derivative provides an instantaneous rate of change. Getting an instantaneous rate of change when the function is known is easy. However, when you’re working with a microcontroller and varying analog data without a known function, it’s not so easy. Our goal will be to get an average rate of change of the data. And since a microcontroller is many orders of magnitude faster than the rate of change of the incoming data, we can calculate the average rate of change over very small time intervals. Our work will be based on the fact that the average rate of change and instantaneous rate of change are the same over short time intervals.