Cheap stereo line out I2S DAC for CircuitPython / Arduino synths

Continue reading "Cheap stereo line out I2S DAC for CircuitPython / Arduino synths"

Continue reading "Cheap stereo line out I2S DAC for CircuitPython / Arduino synths"

Variable-speed playback cassette players were already the cool kids on the block. How else are you going to have any fun with magnetic tape without ripping out the tape head and running it manually over those silky brown strips? Sure, you can change the playback speed on most players as long as you can get to the trim pot. But true variable-speed players make better synths, because it’s so much easier to change the speed. You can make music from anything you can record on tape, including monotony.

[schollz] made a tape synth with not much more than a variable-speed playback cassette player, an Arduino, a DAC, and a couple of wires to hook it all up. Here’s how it works: [schollz] records a long, single note on a tape, then uses that recording to play different notes by altering the playback speed with voltages from a MIDI synth.

To go from synth to synth, [schollz] stood up a server that translates MIDI voltages to serial and sends them to the Arduino. Then the DAC converts them to analog signals for the tape player. All the code is available on the project site, and [schollz] will even show you where to add Vin and and a line in to the tape player. Check out the demo after the break.

There’s more than one way to hack a cassette player. You can also force them to play full-motion, color video.

Via adafruit

[Joekutz] wanted to re-build an audio-rate function generator project that he found over on Instructables. By itself, the project is very simple: it’s an 8-bit resistor-ladder DAC, a nice enclosure, and the rest is firmware.

[Joekutz] decided this wasn’t enough. He needed an LCD display, a speaker, and one-hertz precision. The LCD display alone is an insane hack. He reverse-engineers a calculator simply to use the display. But instead of mapping each key on the calculator and typing each number in directly, he only taps the four 1, +, =, and clear keys. He can then enter arbitrary numbers by typing in the right number of ones and adding them up. 345 = 111 + 111 + 111 + 11 + 1. In his video, embedded below, he describes this as a “rather stupid” idea. We think it’s hilarious.

The meat of the project is the Arduino-based waveform generator, though. In the second video below, [joekutz] walks through the firmware in detail. If you’d like a simple introduction to DDS, check it out (or read up our more in-depth version).

He also makes custom detents for his potentiometers so that he can enter precise numerical values. These consist of special knobs and spring-clips that work together to turn a normal pot into a rough 8-way (or whatever) switch. Very cool.

So even if you don’t need an R-2R DAC based waveform generator, go check this project out. There’s good ideas at every turn.

[Andy] had the idea of turning a mixing desk into a MIDI controller. At first glance, this idea seems extremely practical – mixers are a great way to get a lot of dials and faders in a cheap, compact, and robust enclosure. Exactly how you turn a mixer into a MIDI device is what’s important. This build might not be the most efficient, but it does have the best name ever: digital to analog to digital to analog to digital conversion.

The process starts by generating a sine wave on an Arduino with some direct digital synthesis. A 480 Hz square wave is generated on an ATTiny85. Both of these signals are then fed into a 74LS08 AND gate. According to the schematic [Andy] posted, these signals are going into two different gates, with the other input of the gate pulled high. The output of the gate is then sent through a pair of resistors and combined to the ‘audio out’ signal. [Andy] says this is ‘spine-crawling’ for people who do this professionally. If anyone knows what this part of the circuit actually does, please leave a note in the comments.

The signal from the AND gates is then fed into the mixer and sent out to the analog input of another Arduino. This Arduino converts the audio coming out of the mixer to frequencies using a Fast Hartley Transform. With a binary representation of what’s happening inside the mixer, [Andy] has something that can be converted into MIDI.

[Andy] put up a demo of this circuit working. He’s connected the MIDI out to Abelton and can modify MIDI parameters using an audio mixer. Video of that below if you’re still trying to wrap your head around this one.

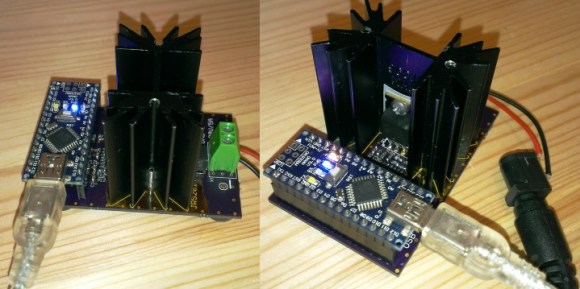

Some projects are both educational and useful. We believe that [Jasper's] Arduino based electronic load is one of those project.

[Jasper's] electronic load can not only act as a constant current load, but also as a constant power and constant resistive load as well. The versatile device has been designed for up to 30V, 5A, and 15W. It was based on a constant current source that is controlled by a DAC hooked up to the Arduino. By measuring both the resulting voltage and current of the load, the system can dynamically adapt to achieve constancy. While we have seen other Arduino based constant loads before, [Jasper's] is very simple and straight forward compartively. [Jasper] also includes both the schematic and Arduino code, making it very easy to reproduce.

There are tons of uses for a voltage controlled current source, and this project is a great way to get started with building one. It is an especially great project for putting together your knowledge of MOSFET theory and opamp theory!

Learn how to use the NXP PCF 8591 8-bit A/D and D/A IC with Arduino in chapter fifty-two of my Arduino Tutorials. The first chapter is here, the complete series is detailed here.

Updated 17/06/2013

Introduction

Have you ever wanted more analogue input pins on your Arduino project, but not wanted to fork out for a Mega? Or would you like to generate analogue signals? Then check out the subject of our tutorial – the NXP PCF8591 IC. It solves both these problems as it has a single DAC (digital to analogue) converter as well as four ADCs (analogue to digital converters) – all accessible via the I2C bus. If the I2C bus is new to you, please familiarise yourself with the readings here before moving forward.

The PCF8591 is available in DIP form, which makes it easy to experiment with:

You can get them from the usual retailers. Before moving on, download the data sheet. The PCF8591 can operate on both 5V and 3.3V so if you’re using an Arduino Due, Raspberry Pi or other 3.3 V development board you’re fine. Now we’ll first explain the DAC, then the ADCs.

Using the DAC (digital-to-analogue converter)

The DAC on the PCF8591 has a resolution of 8-bits – so it can generate a theoretical signal of between zero volts and the reference voltage (Vref) in 255 steps. For demonstration purposes we’ll use a Vref of 5V, and you can use a lower Vref such as 3.3V or whatever you wish the maximum value to be … however it must be less than the supply voltage. Note that when there is a load on the analogue output (a real-world situation), the maximum output voltage will drop – the data sheet (which you downloaded) shows a 10% drop for a 10kΩ load. Now for our demonstration circuit:

Note the use of 10kΩ pull-up resistors on the I2C bus, and the 10μF capacitor between 5V and GND. The I2C bus address is set by a combination of pins A0~A2, and with them all to GND the address is 0x90. The analogue output can be taken from pin 15 (and there’s a seperate analogue GND on pin 13. Also, connect pin 13 to GND, and circuit GND to Arduino GND.

To control the DAC we need to send two bytes of data. The first is the control byte, which simply activates the DAC and is 1000000 (or 0x40) and the next byte is the value between 0 and 255 (the output level). This is demonstrated in the following sketch:

// Example 52.1 PCF8591 DAC demo

// http://tronixstuff.com/tutorials Chapter 52

// John Boxall June 2013

#include "Wire.h"

#define PCF8591 (0x90 >> 1) // I2C bus address

void setup()

{

Wire.begin();

}

void loop()

{

for (int i=0; i<256; i++)

{

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(0x40); // control byte - turn on DAC (binary 1000000)

Wire.write(i); // value to send to DAC

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

}

for (int i=255; i>=0; --i)

{

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(0x40); // control byte - turn on DAC (binary 1000000)

Wire.write(i); // value to send to DAC

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

}

}Did you notice the bit shift of the bus address in the #define statement? Arduino sends 7-bit addresses but the PCF8591 wants an 8-bit, so we shift the byte over by one bit.

The results of the sketch are shown below, we’ve connected the Vref to 5V and the oscilloscope probe and GND to the analogue output and GND respectively:

If you like curves you can generate sine waves with the sketch below. It uses a lookup table in an array which contains the necessary pre-calculated data points:

// Example 52.2 PCF8591 DAC demo - sine wave

// http://tronixstuff.com/tutorials Chapter 52

// John Boxall June 2013

#include "Wire.h"

#define PCF8591 (0x90 >> 1) // I2C bus address

uint8_t sine_wave[256] = {

0x80, 0x83, 0x86, 0x89, 0x8C, 0x90, 0x93, 0x96,

0x99, 0x9C, 0x9F, 0xA2, 0xA5, 0xA8, 0xAB, 0xAE,

0xB1, 0xB3, 0xB6, 0xB9, 0xBC, 0xBF, 0xC1, 0xC4,

0xC7, 0xC9, 0xCC, 0xCE, 0xD1, 0xD3, 0xD5, 0xD8,

0xDA, 0xDC, 0xDE, 0xE0, 0xE2, 0xE4, 0xE6, 0xE8,

0xEA, 0xEB, 0xED, 0xEF, 0xF0, 0xF1, 0xF3, 0xF4,

0xF5, 0xF6, 0xF8, 0xF9, 0xFA, 0xFA, 0xFB, 0xFC,

0xFD, 0xFD, 0xFE, 0xFE, 0xFE, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF,

0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFE, 0xFE, 0xFE, 0xFD,

0xFD, 0xFC, 0xFB, 0xFA, 0xFA, 0xF9, 0xF8, 0xF6,

0xF5, 0xF4, 0xF3, 0xF1, 0xF0, 0xEF, 0xED, 0xEB,

0xEA, 0xE8, 0xE6, 0xE4, 0xE2, 0xE0, 0xDE, 0xDC,

0xDA, 0xD8, 0xD5, 0xD3, 0xD1, 0xCE, 0xCC, 0xC9,

0xC7, 0xC4, 0xC1, 0xBF, 0xBC, 0xB9, 0xB6, 0xB3,

0xB1, 0xAE, 0xAB, 0xA8, 0xA5, 0xA2, 0x9F, 0x9C,

0x99, 0x96, 0x93, 0x90, 0x8C, 0x89, 0x86, 0x83,

0x80, 0x7D, 0x7A, 0x77, 0x74, 0x70, 0x6D, 0x6A,

0x67, 0x64, 0x61, 0x5E, 0x5B, 0x58, 0x55, 0x52,

0x4F, 0x4D, 0x4A, 0x47, 0x44, 0x41, 0x3F, 0x3C,

0x39, 0x37, 0x34, 0x32, 0x2F, 0x2D, 0x2B, 0x28,

0x26, 0x24, 0x22, 0x20, 0x1E, 0x1C, 0x1A, 0x18,

0x16, 0x15, 0x13, 0x11, 0x10, 0x0F, 0x0D, 0x0C,

0x0B, 0x0A, 0x08, 0x07, 0x06, 0x06, 0x05, 0x04,

0x03, 0x03, 0x02, 0x02, 0x02, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0x02, 0x02, 0x03,

0x03, 0x04, 0x05, 0x06, 0x06, 0x07, 0x08, 0x0A,

0x0B, 0x0C, 0x0D, 0x0F, 0x10, 0x11, 0x13, 0x15,

0x16, 0x18, 0x1A, 0x1C, 0x1E, 0x20, 0x22, 0x24,

0x26, 0x28, 0x2B, 0x2D, 0x2F, 0x32, 0x34, 0x37,

0x39, 0x3C, 0x3F, 0x41, 0x44, 0x47, 0x4A, 0x4D,

0x4F, 0x52, 0x55, 0x58, 0x5B, 0x5E, 0x61, 0x64,

0x67, 0x6A, 0x6D, 0x70, 0x74, 0x77, 0x7A, 0x7D

};

void setup()

{

Wire.begin();

}

void loop()

{

for (int i=0; i<256; i++)

{

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(0x40); // control byte - turn on DAC (binary 1000000)

Wire.write(sine_wave[i]); // value to send to DAC

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

}

}And the results:

For the following DSO image dump, we changed the Vref to 3.3V – note the change in the maxima on the sine wave:

Now you can experiment with the DAC to make sound effects, signals or control other analogue circuits.

Using the ADCs (analogue-to-digital converters)

If you’ve used the analogRead() function on your Arduino (way back in Chapter One) then you’re already familiar with an ADC. With out PCF8591 we can read a voltage between zero and the Vref and it will return a value of between zero and 255 which is directly proportional to zero and the Vref. For example, measuring 3.3V should return 168. The resolution (8-bit) of the ADC is lower than the onboard Arduino (10-bit) however the PCF8591 can do something the Arduino’s ADC cannot. But we’ll get to that in a moment.

First, to simply read the values of each ADC pin we send a control byte to tell the PCF8591 which ADC we want to read. For ADCs zero to three the control byte is 0x00, 0x01, ox02 and 0x03 respectively. Then we ask for two bytes of data back from the ADC, and store the second byte for use. Why two bytes? The PCF8591 returns the previously measured value first – then the current byte. (See Figure 8 in the data sheet). Finally, if you’re not using all the ADC pins, connect the unused ones to GND.

The following example sketch simply retrieves values from each ADC pin one at a time, then displays them in the serial monitor:

// Example 52.3 PCF8591 ADC demo

// http://tronixstuff.com/tutorials Chapter 52

// John Boxall June 2013

#include "Wire.h"

#define PCF8591 (0x90 >> 1) // I2C bus address

#define ADC0 0x00 // control bytes for reading individual ADCs

#define ADC1 0x01

#define ADC2 0x02

#define ADC3 0x03

byte value0, value1, value2, value3;

void setup()

{

Wire.begin();

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop()

{

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(ADC0); // control byte - read ADC0

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

Wire.requestFrom(PCF8591, 2);

value0=Wire.read();

value0=Wire.read();

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(ADC1); // control byte - read ADC1

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

Wire.requestFrom(PCF8591, 2);

value1=Wire.read();

value1=Wire.read();

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(ADC2); // control byte - read ADC2

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

Wire.requestFrom(PCF8591, 2);

value2=Wire.read();

value2=Wire.read();

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(ADC3); // control byte - read ADC3

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

Wire.requestFrom(PCF8591, 2);

value3=Wire.read();

value3=Wire.read();

Serial.print(value0); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value1); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value2); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value3); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.println();

}Upon running the sketch you’ll be presented with the values of each ADC in the serial monitor. Although it was a simple demonstration to show you how to individually read each ADC, it is a cumbersome method of getting more than one byte at a time from a particular ADC.

To do this, change the control byte to request auto-increment, which is done by setting bit 2 of the control byte to 1. So to start from ADC0 we use a new control byte of binary 00000100 or hexadecimal 0x04. Then request five bytes of data (once again we ignore the first byte) which will cause the PCF8591 to return all values in one chain of bytes. This process is demonstrated in the following sketch:

// Example 52.4 PCF8591 ADC demo

// http://tronixstuff.com/tutorials Chapter 52

// John Boxall June 2013

#include "Wire.h"

#define PCF8591 (0x90 >> 1) // I2C bus address

byte value0, value1, value2, value3;

void setup()

{

Wire.begin();

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop()

{

Wire.beginTransmission(PCF8591); // wake up PCF8591

Wire.write(0x04); // control byte - read ADC0 then auto-increment

Wire.endTransmission(); // end tranmission

Wire.requestFrom(PCF8591, 5);

value0=Wire.read();

value0=Wire.read();

value1=Wire.read();

value2=Wire.read();

value3=Wire.read();

Serial.print(value0); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value1); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value2); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.print(value3); Serial.print(" ");

Serial.println();

}Previously we mentioned that the PCF8591 can do something that the Arduino’s ADC cannot, and this is offer a differential ADC. As opposed to the Arduino’s single-ended (i.e. it returns the difference between the positive signal voltage and GND, the differential ADC accepts two signals (that don’t necessarily have to be referenced to ground), and returns the difference between the two signals. This can be convenient for measuring small changes in voltages for load cells and so on.

Setting up the PCF8591 for differential ADC is a simple matter of changing the control byte. If you turn to page seven of the data sheet, then consider the different types of analogue input programming. Previously we used mode ’00’ for four inputs, however you can select the others which are clearly illustrated, for example:

So to set the control byte for two differential inputs, use binary 00110000 or 0x30. Then it’s a simple matter of requesting the bytes of data and working with them. As you can see there’s also combination single/differential and a complex three-differential input. However we’ll leave them for the time being.

Conclusion

Hopefully you found this of interest, whether adding a DAC to your experiments or learning a bit more about ADCs. We’ll have some more analogue to digital articles coming up soon, so stay tuned. And if you enjoy my tutorials, or want to introduce someone else to the interesting world of Arduino – check out my new book “Arduino Workshop” from No Starch Press.

In the meanwhile have fun and keep checking into tronixstuff.com. Why not follow things on twitter, Google+, subscribe for email updates or RSS using the links on the right-hand column? And join our friendly Google Group – dedicated to the projects and related items on this website. Sign up – it’s free, helpful to each other – and we can all learn something.

The post Tutorial – Arduino and PCF8591 ADC DAC IC appeared first on tronixstuff.

If a seemingly infinitely programmable mini computer like the Raspberry Pi is just too... limiting, we've got good news: the Gertboard extender has started shipping. The $48 companion board reaching customers' doorsteps converts analog to digital and back for Raspberry Pi fans developing home automation, robotics and just about anything else that needs a translation between the computing world and less intelligent objects. The one catch, as you'd sometimes expect from a homebrew project, is the need for some assembly -- you'll have to solder together Gert van Loo's Arduino-controlled invention on your own. We imagine the DIY crowd won't mind, though, as long as they can find the fast-selling Gertboard in the first place.

[Image credit: Stuart Green, Flickr]

Filed under: Misc

Gertboard extender for Raspberry Pi ships to advanced tinkerers originally appeared on Engadget on Wed, 17 Oct 2012 03:58:00 EST. Please see our terms for use of feeds.

Permalink | Email this | Comments