CB Radio + Arduino = 6 Meter Ham Band

Somehow [hvde] wound up with a CB radio that does AM and SSB on the 11 meter band. The problem was that the radio isn’t legal where he lives. So he decided to change the radio over to work on the 6 meter band, instead.

We were a little surprised to hear this at first. Most radio circuits are tuned to pretty close tolerances and going from 27 MHz to 50 MHz seemed like quite a leap. The answer? An Arduino and a few other choice pieces of circuitry.

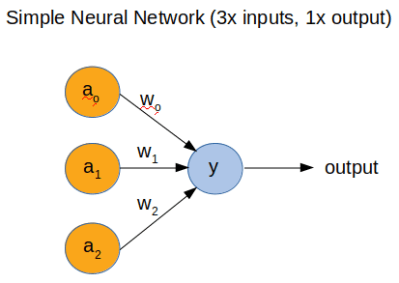

In particular, [hvde] removed much of the RF portion of the radio, leaving just the parts that dealt with the intermediate frequency at 7.8 MHz. Even the transmitter generates this frequency because it is easier to create an SSB signal at a fixed frequency. The Arduino drives a frequency synthesizer and an OLED display. A mixer combines the IF signal with the frequency the Arduino commands.

The radio had a “clarifier” which acts as a fine tuning control. With the new setup, the Arduino has to read this, also, and make small adjustments to the frequency. The RF circuits in the radio took some modifications, too. It is all documented, although we will admit this probably isn’t a project for the faint of heart.

As much as we admired this project, we think we will just stick with SDR. If you want to learn more about the digital synthesis of signals, check out [Bil Herd’s] post.